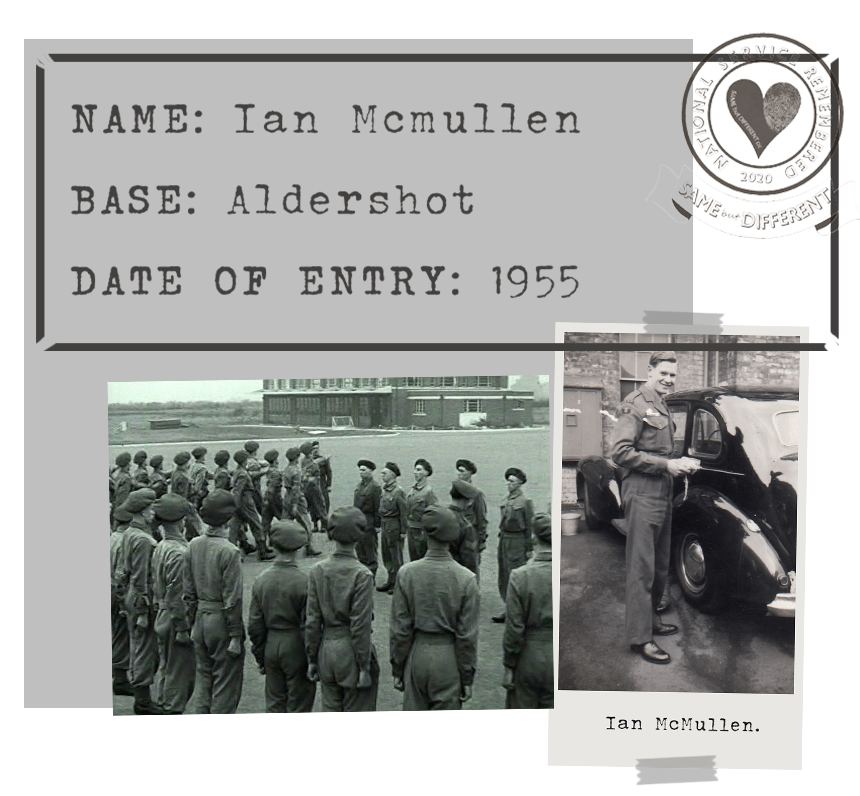

“I became the personal chauffer for the Head of the British Army that was organising the invasion of Egypt.”

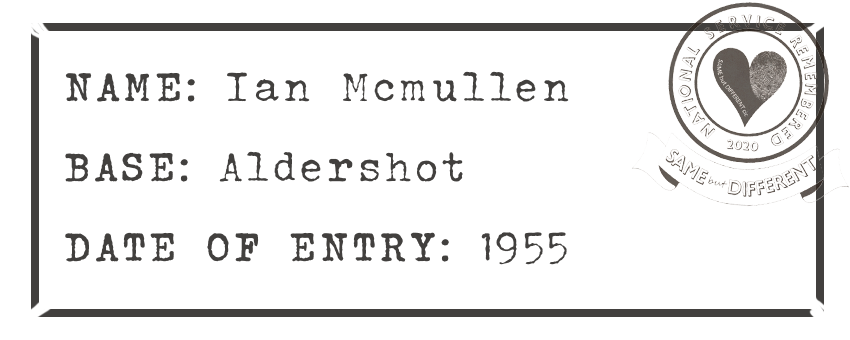

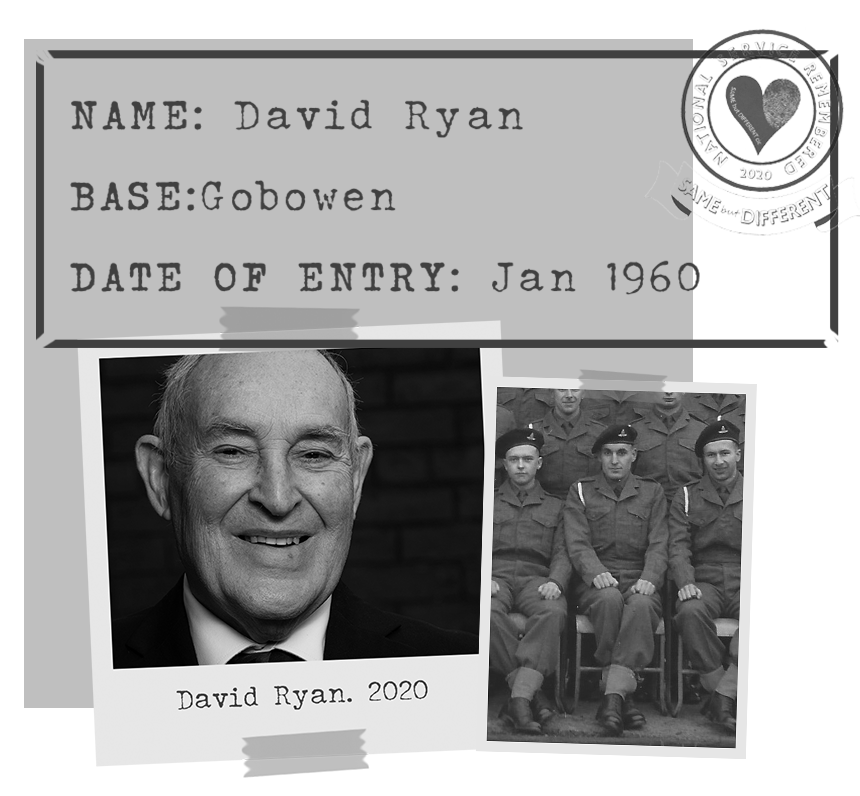

I was called up for National Service from 1955-1957.

I was 18 and still remember my army serial number. At my age, which is 83, you can forget your wife’s name but your army number, you don’t. I was in the RASC “Royal Army Service Corps”, known by some as “Run Away Somebody’s Coming”! We weren’t doing the fighting. It was the transport division and could be up for criticism, it could be regarded as runaway.

I lived on the Wirral and I was called up in January. I had to go to Euston station to travel to Aldershot and did a fortnight’s training there. From there I went down to Somerset and did the summer months’ training there. I was offered a non-Commissioned Officer’s course or go into driving, the chauffeur course, driving senior officers.

I was very fortunate and I had the most interesting time. It was quite severe training to start off with and you met all sorts of people, from all walks of life but you all got on very well after the first few weeks. In those days there were the ruffians, the teddy boys, with their sleek hair, suede shoes and pipe suits who were looking for trouble, and when I got on the train in London, I thought, my god, I’ll keep my head down here, but within three days, when we’d all had the same haircut and we were all in the same clothes and you’re all fighting to survive the onslaught of the NCO, the Corporals and Sergeants who were drilling you, you all pulled together and became good friends.

“Within three days, we’d all had the same haircut, we were all in the same clothes and you’re all fighting to survive the onslaught of the NCO.”

I had been to Boarding school and at school I joined the Air Training Corp so I’d done all this; I’d been to the RAF places and done drill-drill instructions and flying in the Tiger Moth so I was quite aware of the discipline and what was involved. I didn’t have any bother at all but I know there were lads who had actually never been away from home and that first and second night were sitting on their beds, crying their eyes out because they were homesick. They got over it, they had to.

Before I enlisted, I had to go for a medical in Liverpool to this Army-type hospital.

There were hundreds of lads there, all running around naked, being told to do this and do that. Having been at Boarding School, I was aware of all this but some of these lads were totally out of their depth.

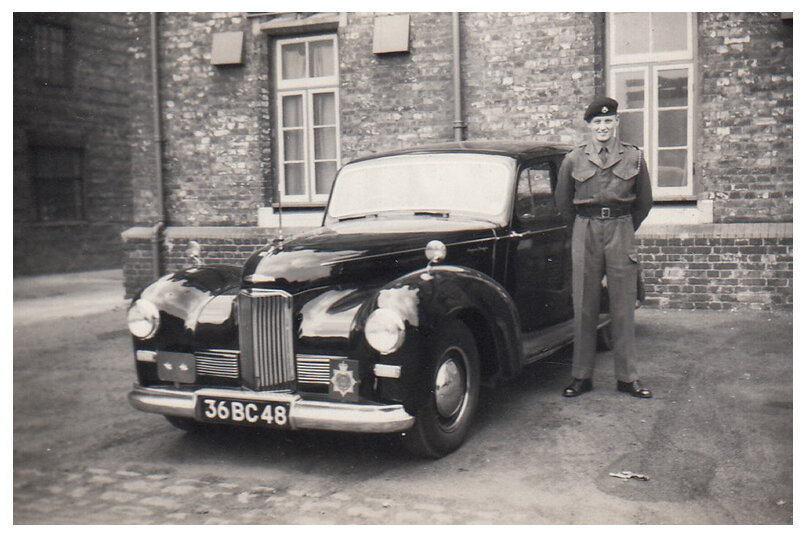

At the age of 18, I’d got my driving licence before I went in the Army but I passed the Army course and went on to 3-tonne trucks, 7-tonne trucks, pick-up trucks and eventually onto Humber, which were the black limousines, with stars denoting the seniority of the Generals, and flags on the bonnet while you were driving. I ended up at the barracks in Regent’s Park, London. I was in a pool of drivers, driving for the War Office Major Generals and above. There were about 8 of us in this pool. We had to go through a course of learning the roads in London and then eventually, when we got used to that, we went on to driving. We were like a taxi service for Major Generals that were working at the War Office.

It was excellent in London because wherever we went with these Officers, with stars on a big black limousine, you did very well indeed. I went up as far as Leeds taking these Generals around the country, inspecting army barracks. It was an interesting time and then the Suez Crisis evolved and I became the personal chauffeur for the Head of the British Army that was organising the invasion of Egypt. He asked for me to go to Egypt; he wanted to take me as his chauffer which was very unusual, but anyway I was kitted out with tropical army clothes, the left-hand drive desert car and all the kit to go to Egypt. Of course, it was then cancelled. He was a full British General and I stayed there until I was de-mobbed in January 57.

“He wanted to take me as his chauffer which was very unusual, but anyway I was kitted out with tropical army clothes, the left-hand drive desert car and all the kit to go to Egypt. Of course, it was then cancelled.”

At the age of 18, I learnt how to kill somebody with a bayonet, how to shoot a rifle 303, a stun gun and a Bren gun.

We had experience in gas, had to wear gas masks and so on. It was quite an experience from 18-20. I look upon my grandchildren now and think they wouldn’t be able to do this. But it was a good experience and I was fortunate enough to have two years of something to do of interest. Friends of mine who had been posted to places like Germany were confined to barracks and that sort of thing and had a pretty boring time.

I was glad to be de-mobbed, I’d had my two years and my father had a business that I wanted to get involved in. You had an opportunity to sign on as a regular for three years and get a regular wage but I was earning 32 and sixpence a week. That’s about £1.12 per week plus expenses and because everything was paid for, I could send money home.

The best man at my wedding was about my age - he joined National Service and went into the Royal Marines, fighting terrorists in Cyprus. Very few National Service men were good enough to get into one of the elite fighting units of the Armed Forces. At one time, I actually drove Lord Ironside who was Chief of the Imperial General Staff at the beginning of the Second World War in 1939. He was about 90 and I had to take him down to Woolwich to a dinner. I also drove a celebrity of the day, a fellow called Wilfred Pickles and his wife Mabel. He had a radio show, a sort of quiz thing, and we used to take celebrities who went on tours abroad, entertaining the troops. They would stay in a hotel in London and then we would chauffer them out to the airport to get on the plane,

One chap, the General who was planning the invasion of Egypt, I would take him to London airport to meet the French General. They were all in civilian clothes, all top secret and in fact I had to go through the security and signed the official Secrets Act. The General from France would come over and I’d pick him up, and my General would say, “right driver, drive around for two hours now”. This was for security reasons so they could talk in the back of my car and discuss their planning without anyone like the press listening in. Then of course I’d take him back to the airport and he’d go back to France.

It was quite to easy to get back into civilian life.

I got back into a routine quickly, I had a job to do and got on with it. Before I went in the Army I was working at home with some saws that needed sharpening so I took them up to the local ironmonger to sharpen and forgot about them. When I came out of the Army, I went back to pick the saws up and the whole place had been demolished and there was a Council Estate built over it. No saws lying around.

Another time, somebody had borrowed a ladder and a wheelbarrow. When I got back, I went round to his house and there was the ladder and the wheelbarrow sitting in his drive, so I put the ladder on the wheelbarrow and took it back.

I learnt a lot in life. In fact, in London, the services used to get the spare tickets for the shows and theatres. We went to some of the television theatres as a member of the audience. We also suffered the terrible smogs of 1955 in London. If you went out, and you couldn’t possibly go out in the car, if you walked along the road, you couldn’t see in front of you so you kept your hand on the wall until you met the end and the corner, and you knew you’d got to the end of the building, it was that thick. Smogs could last for 24 hours and killed a lot of people with chest infections. On the cars, when you pressed your indicator, a little thing popped up at the side of the car with an arrow on it, about six inches long. They were stopped and they started to put flashing lights on the corners on the car.

The interesting thing is that the limousine in London drove 9 miles to a gallon of petrol and the average speed in London in those days was something not much above that. The roads were so congested, so you had to learn all the little back roads; you didn’t go on the main road, you went through all the side roads in the city. It was very busy.

“I was fortunate enough to have two years of something to do of interest. Friends of mine who had been posted to places like Germany were confined to barracks and that sort of thing and had a pretty boring time.”

Up to last Autumn I was cycling around eighty miles a week.

I don’t cycle as much these days though as I had a hip replacement last year and a cataract replacement just before Christmas. We used to do a hundred miles a week. I’d regularly do a hundred miles in a day for about twelve or fifteen years, in the summer, not in the winter. We would always go to pubs and there could be anywhere between eight to twelve of us at this time around the table. The people around us would say “are you cyclists?” and we’d say “no, not really, we’re going to a fancy dress party”. You knew very well that they were sitting there ear-wigging, listening to what we were saying, and somebody would say “what time did Matron say we’ve got to be back?”. One chap in the pub that I went to said “oh you’re a cyclist, how far have you come?”, I said “from here, it’s about 34 miles”. He was in a very smart open top BMW sitting outside, he asked “what else do you do?” and I said “I like to swim too”. He said “good lord, do you mind me asking you how old you are?”, I said “age has very little to do with it, the fact is, I will tell you, I was born six months before Edward VIII abdicated in favour of George VI” and he sat there and said “good lord, really, that’s amazing, you look absolutely marvellous for 123”.