“You were there to obey orders and look after yourself and - at 18 - it made me realise that I had to grow up.”

I was 5 when the war kicked off and I was bombed out 3 nights on the trot.

We were walking up to my uncles and we got bombed out of there. I used to run around with no shoes on playing in the gutter, but it never did me any harm. I’d go round with an old cart and collect jam jars and I used to get a penny for them. Me and my mates used to go round the grids outside the shops with a stick and some chewing gum for a ten pence piece or half a crown to go to the pictures. But life was so different. I didn’t have any qualifications but my brother got me into the Butcher’s, so I used to go all around Liverpool on a bike. It was freedom, getting out with the basket and getting stuck in the railways lines and the basket would go all over the place. I lived with my mum and dad and the family. We had a double house, top bedroom and middle bedroom. My dad had left home at 15 and went on the sea, ended up as a Bosun but came out of that and on to the docks. I came from a family of 10.

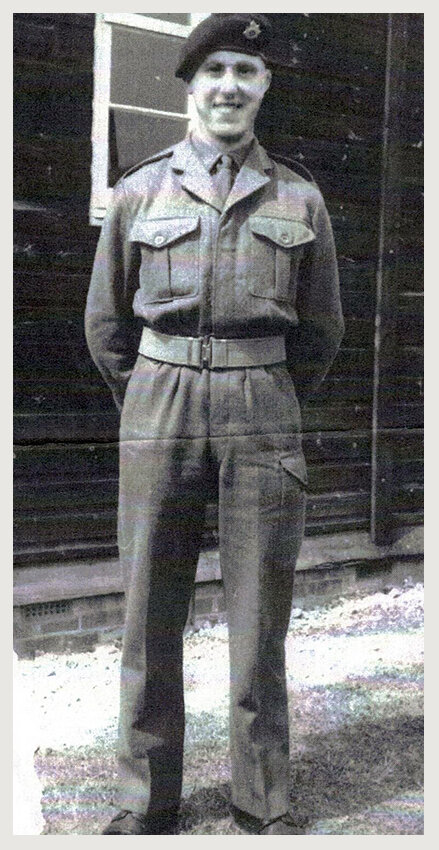

I enjoyed my life. I was a bit of an earwig, doing this and snatching that, but when I went in the army I stopped and just got on with my life. I obeyed orders and all that jazz. You always get threatened, “you’re in my squad and you will not do things that you shouldn’t do”. And if you’ve got someone who can’t march and he’s walking with his left leg instead of his right, it’s murder.

“I was a bit of an earwig, doing this and snatching that, but when I went in the army I stopped and just got on with my life.”

I was 18 when I joined in 1955 and did two years. It never really bothered me because I’d already been in work and I was well averse to what was going to happen. I was a teddy boy before I went in but the forces put a stop to that. It made you realise what you were doing and that it was unacceptable.

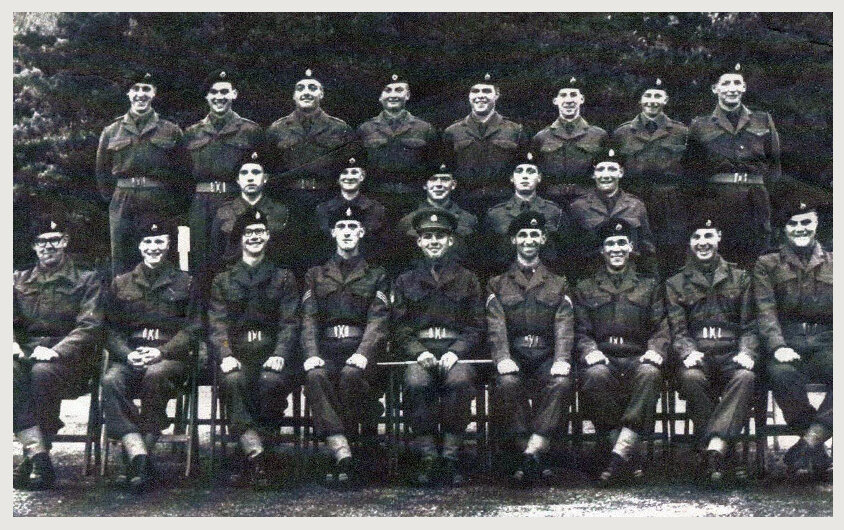

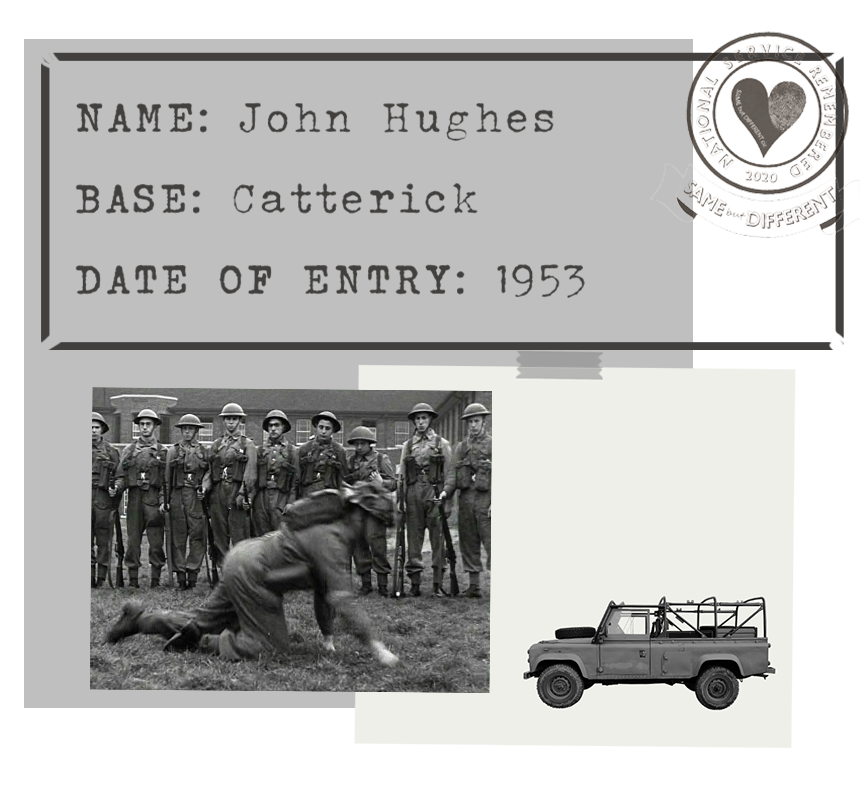

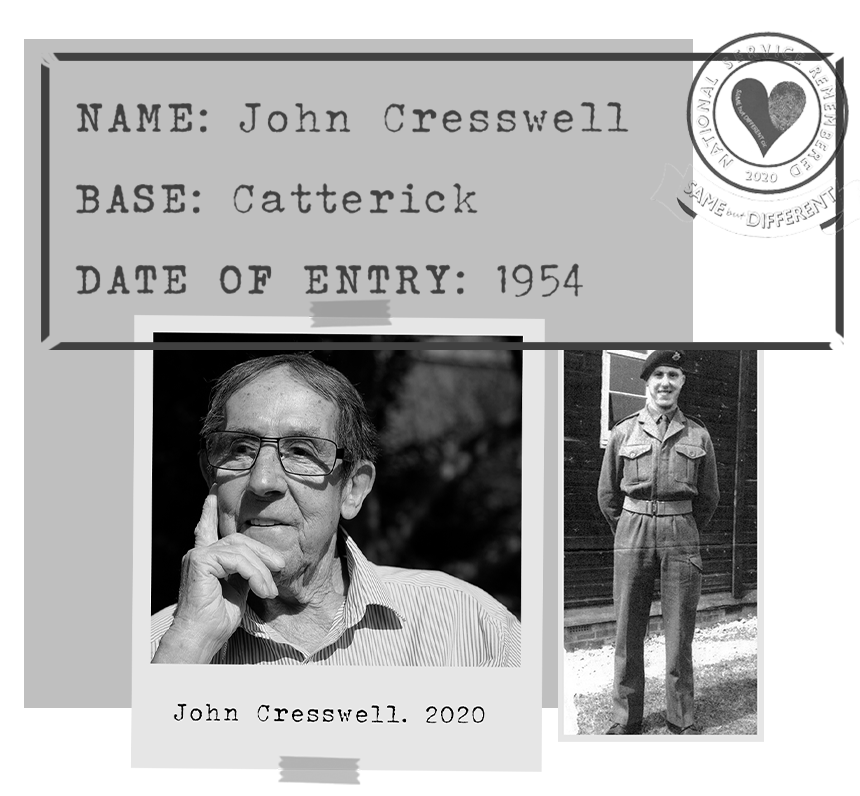

They interviewed me and then I got a letter from Government telling me where I was to report to. I went to Blandford, did 12 weeks and then I was posted to the 41 company in Catterick. You had to learn how to obey orders and be able to look after your clothes.

You had to do this and do that and clean your boots.

It was like that for the first few weeks but you got used to it and when the Sergeant Major came in and started banging the beds shouting “Get up!”, you knew how life was going to be in the forces. You were there to obey orders and look after yourself and, at 18, it made me realise that I had to grow up and accept all the responsibility that was getting thrown at you. We used to get people going AWOL, but not the crew that I was with in Catterick.

After 12 weeks they put you through all your lessons on driving cars. You would do driving in the morning for the first week and all your maintenance in the second week. I had a bren gun in my cab, because they were smaller. You only got a shot round, called a yard. And then we went on night driving which was brilliant. I used to go in the front of the crew in the armoury van, the wagon, and I’d have my headlights on and all the others used to follow my truck. They would see a little light on the rear axle and had to drive like that watching that light, driving in the dark through forest. It was excellent.

I stayed in Catterick for a while and I was given my own vehicle and I had to do its MOT. I had to check all the wheels, do all the greasing and polish my wagon, and it made you take a lot of interest and care in what you were doing. That was the idea of the forces, it was to make a man out of you. If it wasn’t done properly, I’d get square-bashing or they’d put me in the clink, so it made you think and stand up for yourself. Any repairs would need to be reported to the REME that was on site and they would repair it. You would get into trouble if you hadn’t spotted them. Never happened to me. I decided that I was going to do my training, do my two years and that would be it. I came out with no marks of disgrace. Then when you came to do your final test, they would take you to a pyramid and you had to park your car or wagon on the top, neither moving forwards nor backwards. When you achieved that, then you went in for your test and that’s when they took me down to Poole in the middle of summer and I was driving a 10-tonner, but it was great.

“That was the idea of the forces, it was to make a man out of you. If it wasn’t done properly, I’d get square-bashing or they’d put me in the clink, so it made you think and stand up for yourself. ”

Either the Sargeant or the Corporal would come in and bang on the beds shouting to get up.

You had to get up, have your wash and shave and get dressed up properly with your BD (battledress) on. I think you would go for your breakfast and then on parade. You had the camaraderie of all your mates in the army and your billet. When you finished, around about 5 o’clock, that was your free time, unless you were on guard. You used to go into the NAAFI, have a few drinks and perhaps play darts. You had a good life in the army.

After Catterick they subpoenaed me to the medical corp to go on the ration truck with a Corporal. We had to go and pick up the all the food and deliver it to where it was going. I thoroughly enjoyed the ration truck because, being a butcher, I knew what the cuts of meat were and what I had to get. I would say I got a plum job out of this because, being on the ration truck, I didn’t have to go on guard duty.

I used to take about thirty or forty trainees up to the rifle range doing signals and wait for them to finish. Being a trainee myself and gotten over the twelve weeks, I used to feel sorry for them getting shouted at but that’s the only way they could get into your brain, coming from civvy street, you had to learn how to obey orders. I think that did me the world of good.

I enjoyed the camaraderie, backing your mates up all the time.

In the army, your boots would be all pimpled on the toes and they had to be taken out and polished up, so you used to heat a spoon handle over a candle and rub all the pimples out on the toecap and then you had to polish it. ‘Spit and polish’ and you had to see your face in it. Someone would be looking at you and going to pieces because he couldn’t get his boots shiny so you’d pitch in and give them a hand. And on inspection, if they hadn’t made their bed properly or folded their sheets properly, they’d get into trouble again so you always helped people. It was brilliant.

There was no animosity at all that I ever came across in the army. Never. You couldn’t go in the town if you were a fighter though because they wouldn’t wear it, you’d be thrown in jail. You had to respect other people so the army taught you to be that way inclined, the army taught you to respect, to be a good citizen.

You used to come home on a furlough but it was different for me because while I was in the army, I had a letter off my dad to say that they were going to emigrate to Canada, on the £10 passage, and asked if I had any objections to it. I couldn’t object to my parents going away, I was in the army, so I said “yes, you go ahead and I might follow you when I come out of the armed forces.” I didn’t, I stayed in Liverpool. I met my wife and we got married - we’ve been married now for 62 years.

I went out to Canada in 1972. I hadn’t seen my mother and father for about 18 years. My wife worked two jobs for us to get the money to go there and my mother-in-law looked after the children. 18 years had gone before I’d seen my mother and it was fantastic. Two weeks after we came home, I got word that my mother had died. She’d waited all that time to see me before she went.

“Someone would be looking at you and going to pieces because he couldn’t get his boots shiny so you’d pitch in and give them a hand. ”

I used to sing, all over the place, Canada and America.

One time I was in Canada, a millionaire said “I could put you on the circuit, all the clubs”, but I had children, I couldn’t afford to just up and go singing. I used to sing Nat King Cole.

When I came out of the army, I went back to being a butcher and I was put on emergency reserve for 2 years. I was on a bus one day and somebody had a radio. I heard they were calling the troops up to the Suez Canal and I said to myself, this is me now, I’m going to Egypt but they never called me so I was fortunate in that way.

I thought I’d missed out on something. I had to report to the Territorial Army place. I used to teach fellas to drive buses. There was one particular time up by Liverpool airport, and I said to the guy “just stop here, all you’ve got to do now is go down to the roundabout and where the road goes straight, I want you to go around that way onto the road, do you understand?” He said “yes”, kicked the brakes off and went right over the roundabout; he didn’t go around it, he went right across it.

There is no National Service and I feel sorry for the younger people of today because they’re just milling around or getting into trouble and fighting. I think they should, at least, do 12 months, like in Israel. It would give them something to look forward to.

But I definitely think, without a doubt that the forces did me proud, they made me realise that I was an adult, I had to stand on my own two feet and make my own decisions without affecting anybody.