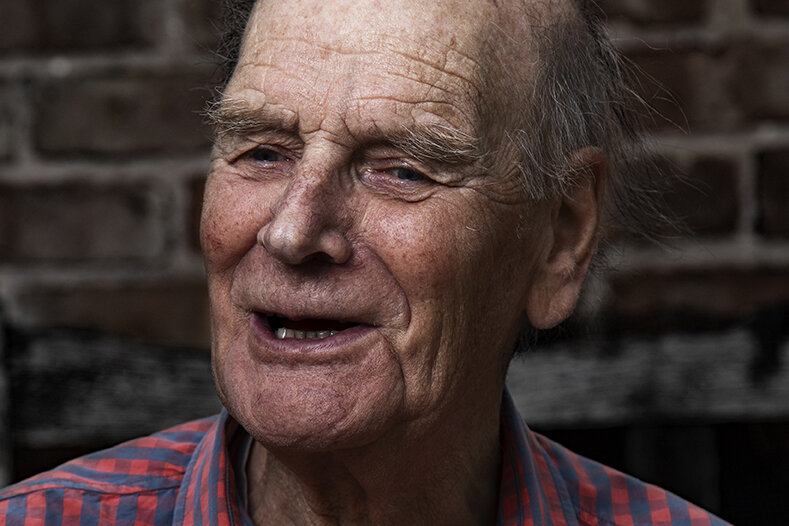

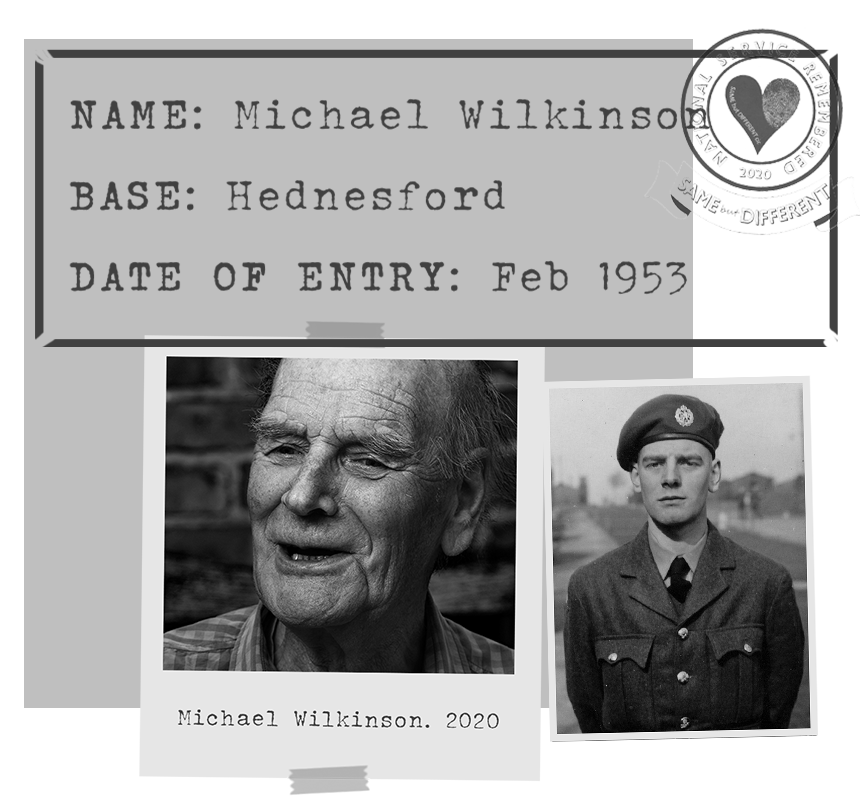

“I think National Service was a very positive experience - it wasn’t easy but I learnt a great deal.”

I look back on it as being a very positive experience.

I get the impression that the majority of people don’t quite see it like that - it was a bit of a bind and they were bored but I was fortunate in that I didn’t go in at 18; I didn’t go in until I was 19½ and I’d already left home (I left home at 16). I went to live in a hostel and so I was used to living away from home.

In a way, I looked forward to National Service but I didn’t go in straight away because I was in the civil service in the forestry commission and I had the opportunity to take exams. Because of this opportunity, they put it back until I was 19. Therefore, I was quite different from everybody else who turned up because I know, with the square-bashing, there were an awful lot of tears every night, people were really, really fed up. And in fact, whilst I was doing square-bashing, there were rumours that there had been two suicides. There were a lot of suicides around this.

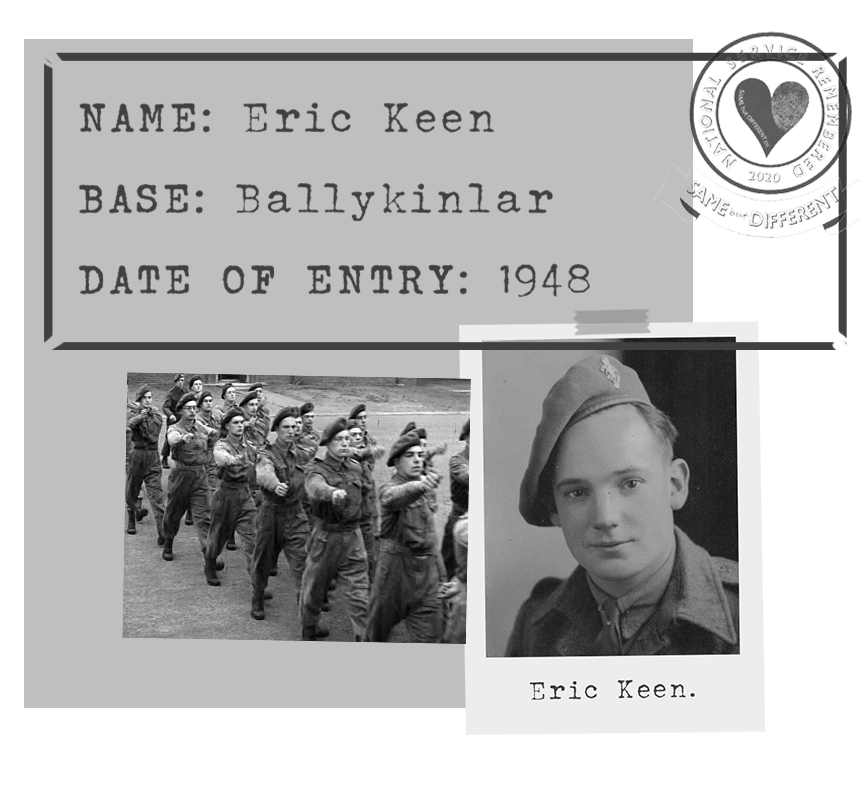

Square-bashing meant learning discipline, learning to march and run and do exactly what you were told. There was an interesting thing that happened to me whilst I was doing that because we were all lined up as we usually were and being inspected by an Officer. This Officer who came along was a school mate and he recognised me. He said “Ah yes, Mr Wilkinson” and I said “yes”, and I called him by his Christian name. Of course, I really got into trouble for that. Put on fatigues for that and sent to the Cookhouse.

“This Officer who came along was a school mate and he recognised me. He said “Ah yes, Mr Wilkinson” and I said “yes”, and I called him by his Christian name. Of course, I really got into trouble for that.”

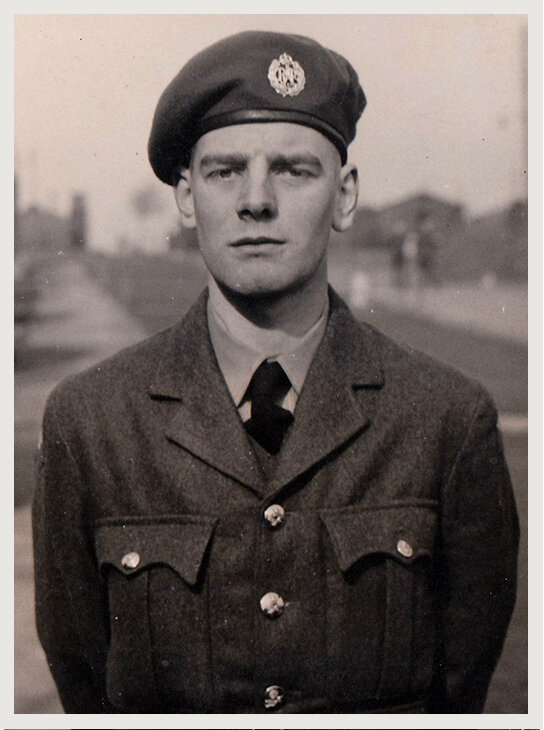

I started on the 24 February 1953. I was given a train ticket and went from London to Padgate which is in Warrington and we were there for about a week. I’d never travelled north before because I was brought up on the south-coast of Portsmouth and spent most of the war years between Bristol and Bath and I’d never been north of Bristol. So we ended up at Warrington and I remember going through this countryside, particularly in Shropshire and thinking this is absolutely wonderful. We got to RAF Padgate and, over several days, we were given uniforms and taught a bit of discipline and we were there for a week.

I remember, at the weekend, we went to Manchester and that was a completely new experience for me.

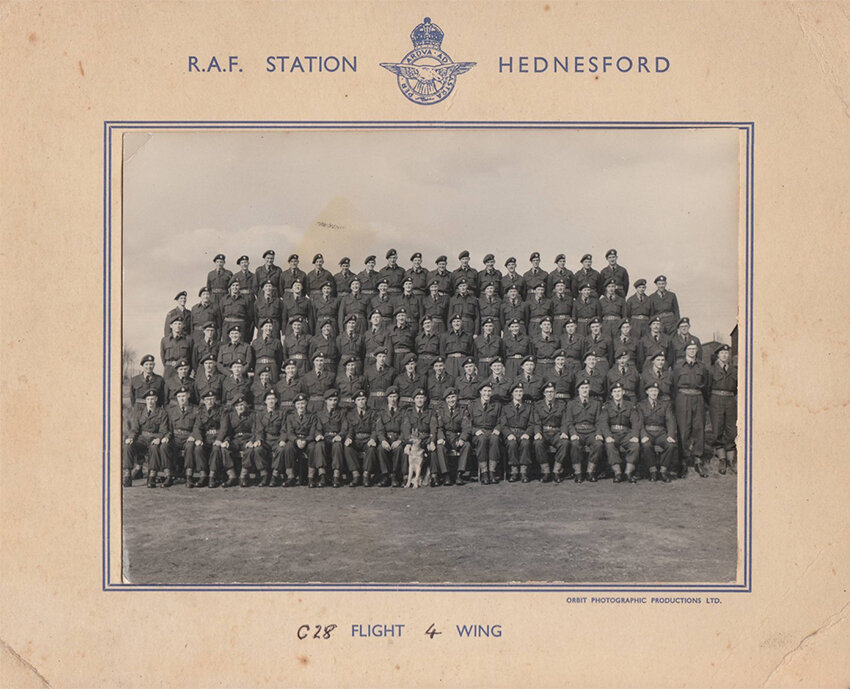

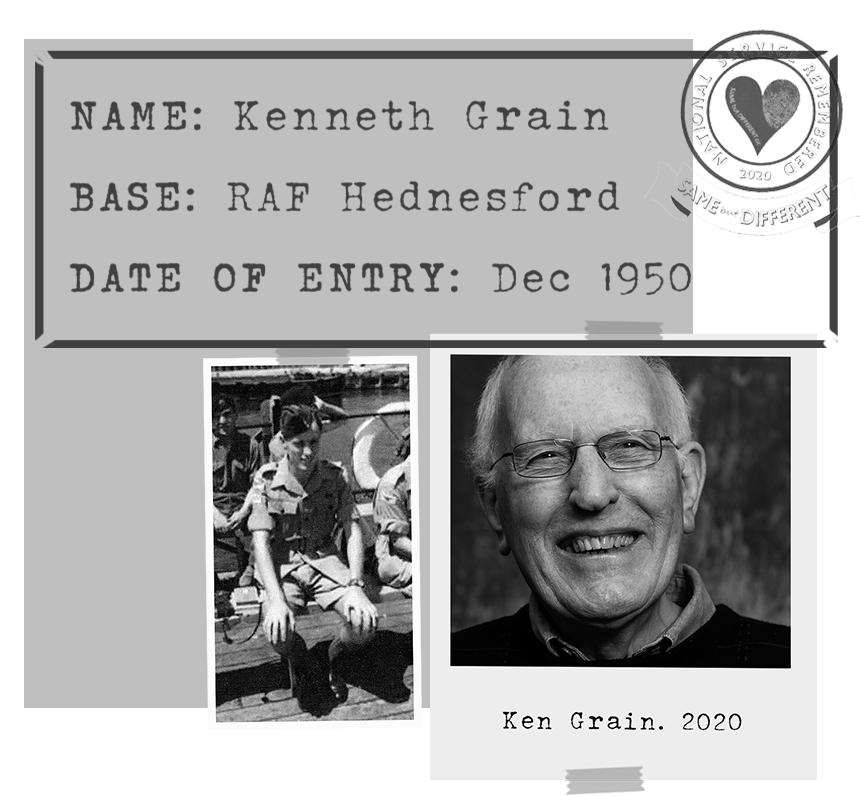

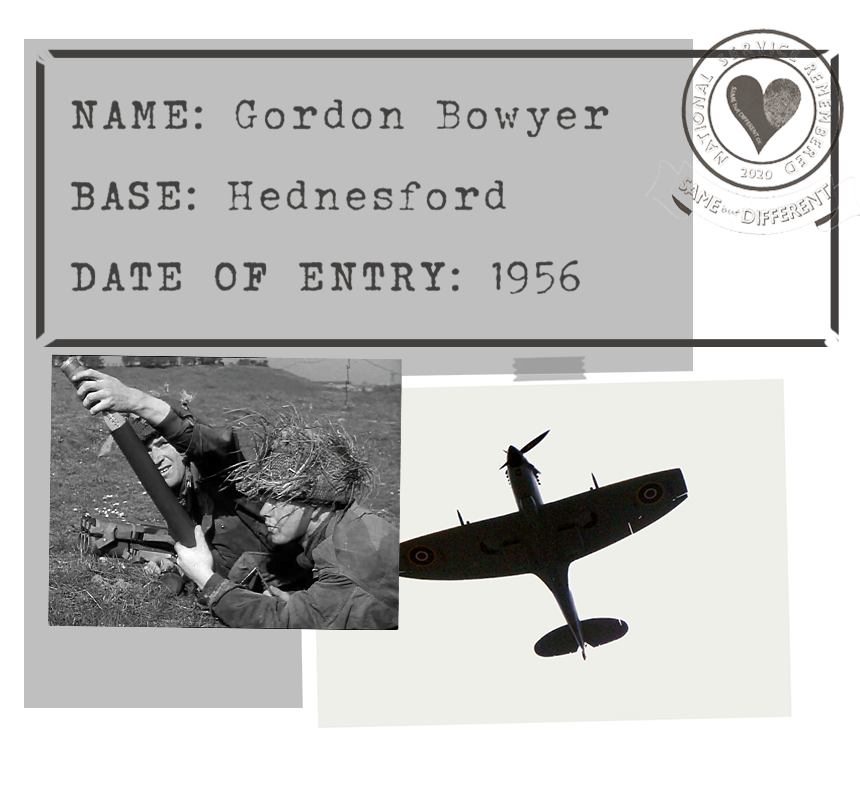

What surprised me was the friendliness of the people compared with London. I’ve never forgotten that. So, we went from Padgate to Hednesford in Staffordshire to do our the basic training and were there for 8 weeks. They just shouted at us everyday and the whole time we were absolutely whacked. This is where I have strong memories of people crying, not being able to cope with leaving home, so it was really, really tough. Anyway, I enjoyed it.

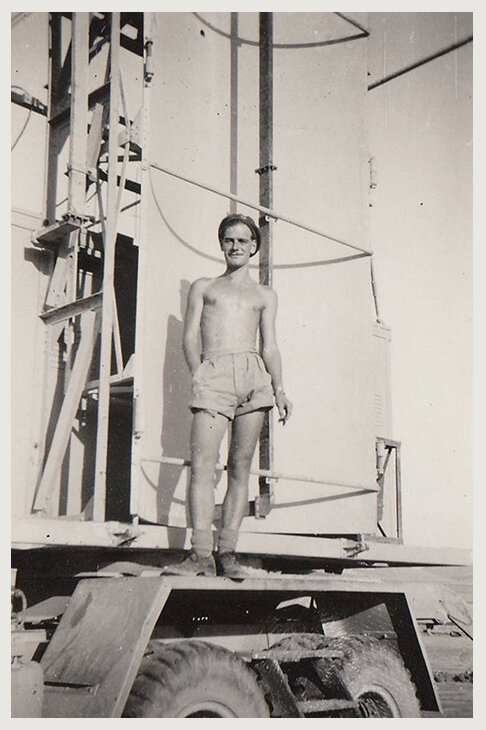

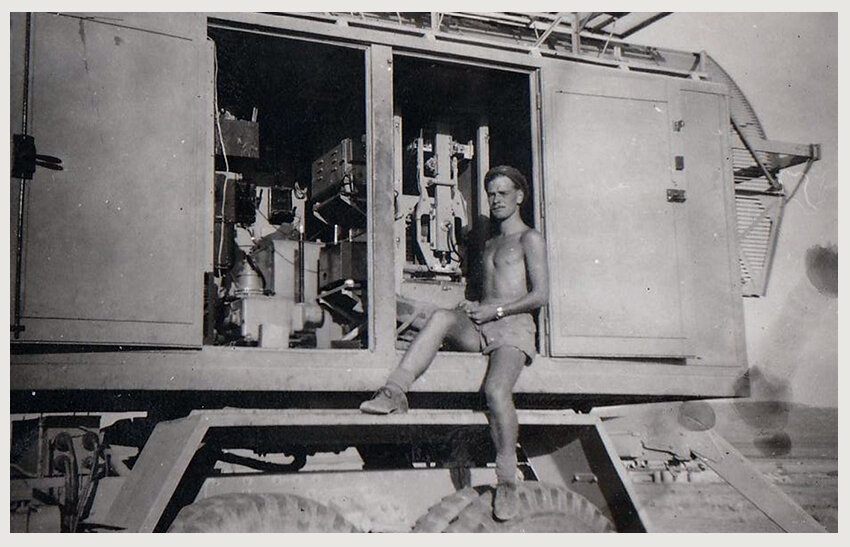

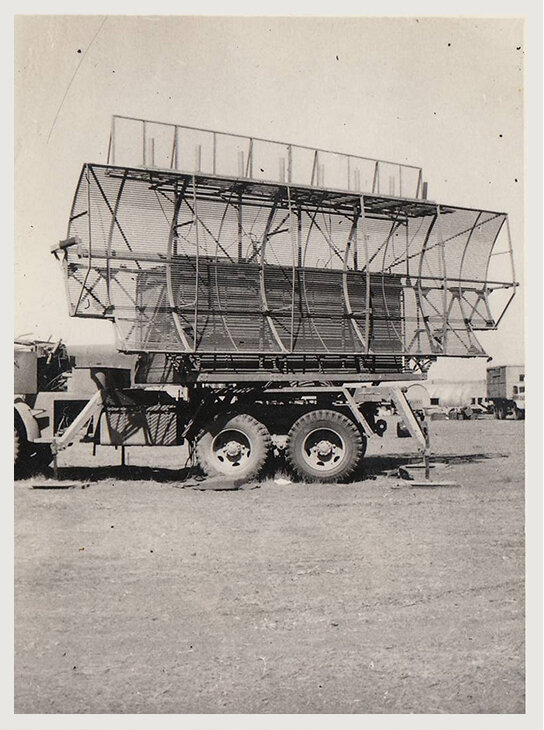

Then they said “what do you want to do?”, and I said “something to do with looking after motorcars or lorries’ maintenance”, so they decided I should be a radar mechanic and I was also what they called a POM, which is Potential Officer Material. I interviewed for that and they said “yes, well you can go on the Officer course but you need to sign on for 4 years” but I wasn’t willing to do that. So, I went to a place called Yatesbury and I was trained there as a radar mechanic. The interesting thing about that was the training was for what they called a centrimetric radar (CMS). It was very high frequency and you stand next to it because it was operated by a thing called a magnetron. It was invented during the war - they tried to make sure that the Germans didn’t know about that particular sort of radar and they went to enormous lengths. The magnetron then became famous as the centre of the microwave oven. After that, they asked me if I wanted to go abroad and I said I’d be quite happy to do that so they posted me to the Middle East to the canal zone.

“They just shouted at us everyday and the whole time we were absolutely whacked. This is where I have strong memories of people crying, not being able to cope with leaving home, so it was really, really tough. Anyway, I enjoyed it.”

After a relatively short time, we were sent to RAF Amman in Jordan.

We flew there and that was quite different. We got on very well with the Jordanians and King Hussein used to come to the camp very often. I was quite happy about that because I found that the money they paid you, which was 28 shillings per week, was very low indeed and it was half of what they paid the regulars, so if you went to the Middle East, they paid you what was called LOA which was Local Overseas Allowance and that was 3 shillings extra per week. So we went to the canal zone and I hadn’t appreciated until I got there that we were in a state of semi-war and all the army stations and the RAF stations all had extensive arms. You stayed inside almost all the time and we were on guard 12 hours or 24 hours, trying to protect the outside of the stations. I went to a place called Abyad which is next to the RAF station at Fayid. When we flew out there I remember flying across Egypt in this Handley Page Hastings and we looked down and saw the Pyramids, which was completely new to me. Abyad was called 109 maintenance unit, 109 MU.

We had a swimming pool there, and our billet, I should have mentioned, was in the canal zone. I was in a tent at the time and there was three of us in a tent. The thing I remember was, they had the Officer in Command one day coming round inspecting us and you had a little card on the tent pole that said your name and your rank, and your number and your religion. I had written ‘Agnostic’ and the Officer saw this and said that he wanted to talk to me. He said “you can’t be an Agnostic” and I said “why not?” He said, “oh no that wouldn’t go down well”. I said, “well I am an agnostic”, so he said, “well just for today be C of E for when the Officer comes round.

So we went to Amman and that was great.

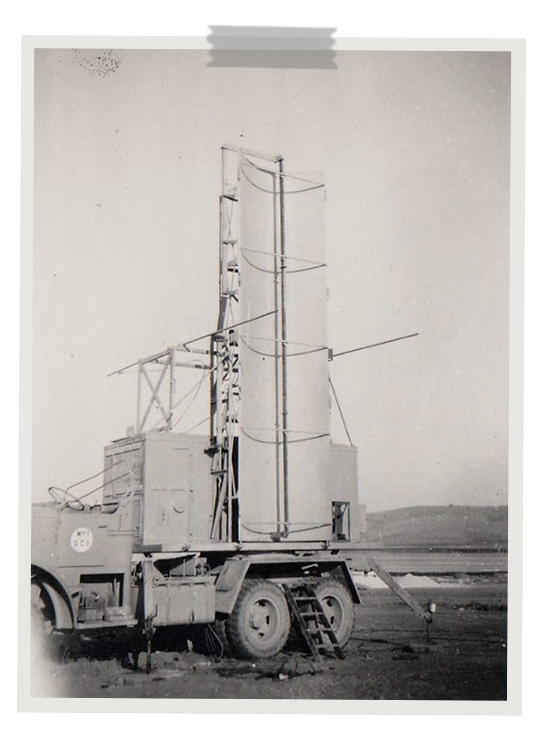

We only worked in the mornings because of the temperature. The sun was low early in the morning until about midday. Anyway, we were working on what they called this mobile centimentric radar system which had a couple of aerials on. One of them spun around, one gave us the distance and the other gave the height. Then they decided that we should move to Habbaniya in Iraq, west of Baghdad, so we flew to Habbaniya which was a super-duper place, it was massive. Again, we were put in tents and then they had this, what you call 123 signals unit out in the desert, some way from the actual RAF and they used to go out there everyday just for maintenance on this unit that moved around. I stayed there until the time I came home. I remember I went to a horse race-track, just outside of Baghdad and put some money on a horse; I’d never done it before in my life and it won!

I remember being in Jordan in Amman on my 21st birthday. It was the 15th September which was the Battle of Britain day - we had a parade and were given the day off. I remember going to the NAAFI and playing darts and it was the first and only time I’d had 3 treble twenties.

Whilst in Amman, five of us got together and arranged transport so that we could spend a day in Jerusalem which was about 50 miles away. I remember passing the Dead Sea on the way there and being impressed by its appearance. Jerusalem itself was a great pleasure: we visited Dome of The Rock, Church of Gethsemane, Via Dolorosa, Mosque of El Aksa and viewed the Mount of Olives. Everyone was extremely friendly but we were warned to be careful if we were on a high or exposed place because we might be shot at by the Israeli’s. I only learned recently that the Jews had had a conflict with the Jordanians, had lost and were banned from almost all of the old city of Jerusalem. This would explain the use of guns.

“I remember going to the NAAFI and playing darts and it was the first and only time I’d had 3 treble twenties.”

I got a medal for serving in the Canal Zone.

It only came out relatively recently and I certainly didn’t expect that. The Canal Zone was tough, quite a few people died and we were under quite a lot of stress.

So then I flew back to Egypt and then we went up to Port Said and caught a boat which was called the Empire Halladale. We were on that for three weeks and that took us back to Liverpool. I’d never been to Liverpool before and it was quite impressive coming into the docks. Then I went down to RAF Innsworth in Gloucestershire where they de-mobbed me, and that was the end of that.

It’s difficult to say if I was sad to be de-mobbed because I had this ambition to be an Officer. I had a thing about aircraft and I fancied myself as being aircrew but I didn’t feel sufficiently confident that I’d get through the course. But when I got back I found it very difficult to adjust so I went for an interview at RAF Hornchurch in Essex and they said we’ll take you on to be an Officer, Air crew, but you have to sign on for 8 years. Again, I felt a bit insecure because if I signed on for 8 years, there was only one thing that I could do afterwards which was to become a civil pilot. That wouldn’t be good if I wanted to get married and have a family so I decided I would forget all about it. I stayed as a civil servant in the Forestry Commission.

Overall, I think National Service was a very positive experience. It wasn’t easy but I learnt a great deal.

If kids today had to do National Service, I think it would be perfect. I think anything that provides discipline is great but they would find it tough. It really is tough and I can understand why a lot of people were crying. I remember finishing the square-bashing, the basic training, and going home to Portsmouth and marching up and down in the kitchen thinking ‘I’ve never ever felt so fit in the whole of my life, this is absolutely wonderful.’