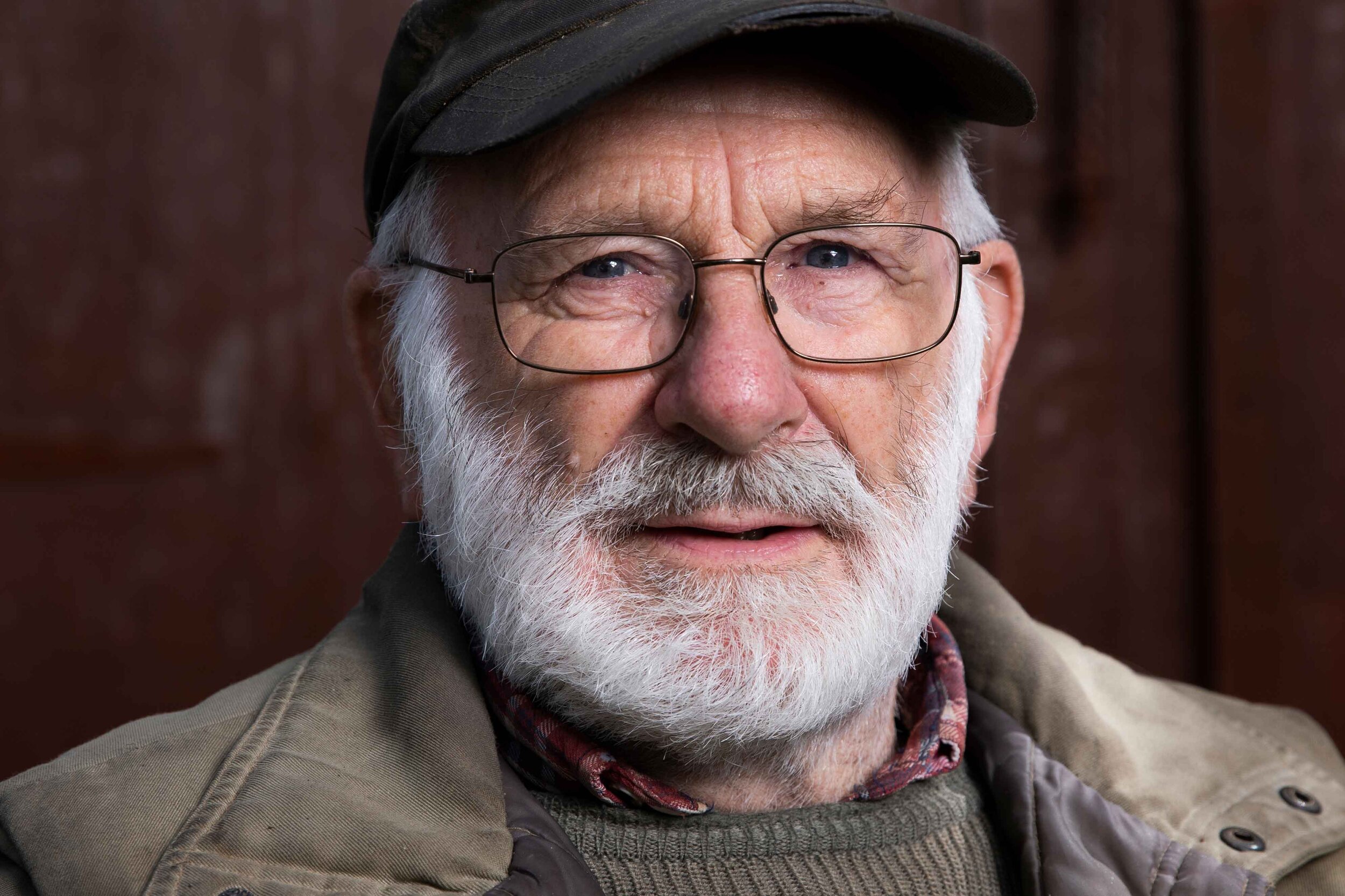

I was born in Shaftesbury - 20th November 1937.

I went to school at the Secondary Modern in Shaftesbury and when I left school, I did a 5-year apprenticeship as a bricklayer. My first bit of brickwork is in Shaftesbury High Street. Underneath the last brick, there’s a tin with a piece of paper showing all the names who were on that job and it's still there to this day, from 1952.

We had about 70 blokes on the firm and they were going off left, right and centre, all the apprentices going off on their National Service, so I didn’t worry about joining, I just went. And I enjoyed myself. I was deferred for two years because of the apprenticeship.

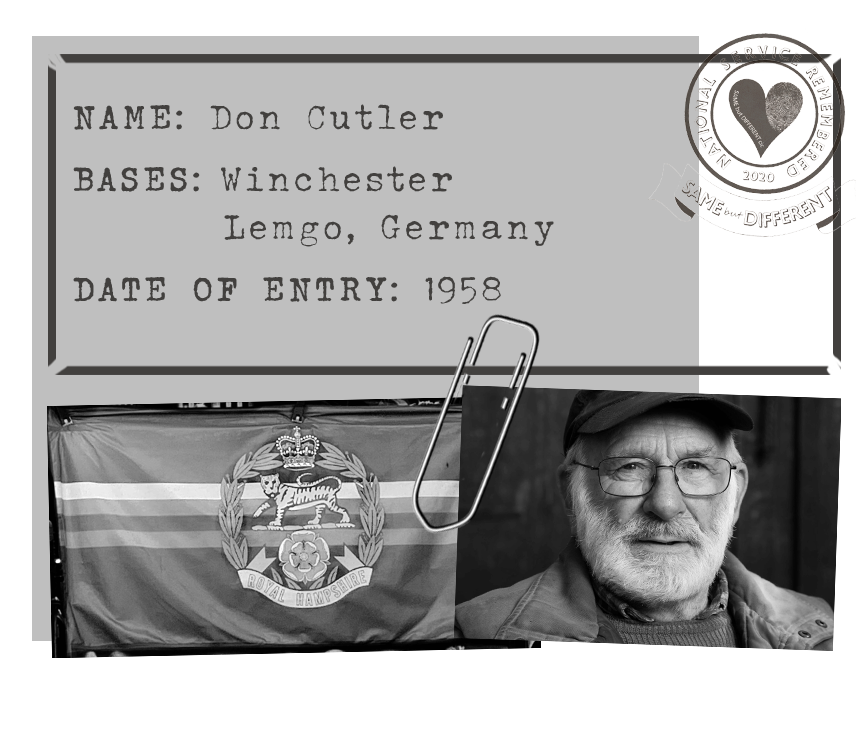

I was in the Royal Hampshire Regiment in Winchester, which is an infantry battalion. They then amalgamated with the Queen’s Regiment to become the Princess of Wales Royal Regiment. The Princess of Wales was our Colonel in Chief and that’s why, when she died, they became the Princess of Wales Royal Regiment.

When you did your training, there was no point getting bolshy, you had to do what you were told. If you didn't, you had to go down and do press ups in the middle of the square with everybody watching you. You didn’t do it again after that.

“We had about 70 blokes on the firm and they were going off left, right and centre, all the apprentices going off on their National Service, so I didn’t worry about joining, I just went. And I enjoyed myself.”

I did my training in Winchester then we got moved over to Germany. We went over on a flat bottom troop ship which had been sunk three times during the war and re-floated. The sea was a bit rough and it would come up and go down with a bang, and that shudder would go right through the ship. Everyone was moaning and people being sick all the time. But we got over there and then we got on the troop train in Holland, which was all wooden seats, and travelled through to Bielefeld. We were then off-loaded and had army lorries to take us to a little town called Lemgo, which was an SS troops barracks, that was all heated by steam; radiators were heated by steam - if you put a damp towel on it now, 5 minutes later it will be bone dry with scorch marks on it.

We were called armoured infantry because when we got over to Germany, we were in Saracens, six-wheel drive armoured personnel carriers, and we’d be all shut in because the Cold War was on.

We had special filters on the Saracen so it filtered the air. We were roaming around all over Germany but we never saw much of it because we were always shut in. Being a six-wheel drive it’d go quite well in the mud and all the ruts of the forests. The tanks had a 12’ track span and left nice big ditches where the tracks were – the Saracen’s were only 10’ wide so we slipped from one track to the other, backwards and forwards. There were 8 men in each Saracen and the driver and commander up on the top. Once, our Saracen did a six-wheel slide sideways and went down in a ditch, right over on its side. I didn’t know what happened. The ones up on the top fell on top of us. They had to get the back door open and, because the door was an inch thick, they had to put pressure on it, and somebody stood on my face with hobnail boots leaving me with stud rash. I had scabs for weeks.

I was a Marksman on the rifle, bren gun and sten gun. Then we moved on to Sterling machine guns and carried a 3.5 rocket launcher. We were on patrol on the iron curtain. Two patrols would go out on the wire, one would go left and the other go right for 10 miles, meet up with another patrol coming the other way, they’d radio back into base, say that they’ve met and then turn around and come back into base camp, which was up in the mountains in a wood. There was 5’ of snow on the ground; that was hard work walking in that stuff. We all dressed up in whites because of snow but when you look at the patrol from a distance through a pair of binoculars, all you could see was a row of black boots going up and down, we never had white boots. If you swing round and look at the guard posts on the Russian part, you could see following that patrol around, with machine guns.

Later on, I did an ammunition train guard up to Berlin with 300 tonne of ammo on board and we got told every time we pulled into a stop there we had to get out. Our car was right up behind the engine and we had to patrol the train both sides because there were men who wanted to go into West Germany. When we came back from Berlin, they were all jumping, trying to get on board and we had to get them off with the back of the rifle. There was a time when West Germany was better off than East Germany. You could see the houses that have been rebuilt in West Berlin and then look through into East Berlin, where none of the damage had been fixed, so they were always behind the times. It was a better life in the West.

“There was 5 feet of snow on the ground; that was hard work walking in that stuff. We all dressed up in whites because of the snow but when you look at the patrol from a distance through a pair of binoculars, all you could see was a row of black boots going up and down, we never had white boots.”

Off duty, we were in a small town called Lemgo.

They had a cellar that we could go down into and have a few beers, it was nice and quiet. We never had much money, National Service was only 25 shillings a week and some of that had to pay for cleaning your gear and equipment, and I used to send home 10 shillings to mum; she kept it for when I came home on leave to go to the pub.

Out in Germany, the cookers were like a kettledrum and had a spring-loaded lid. You would tip in your washed cabbage and potatoes, pull the lid down and close it with the clamps around the edge. Being a regiment of 800 blokes you had to put quite a lot in there. You close the clamps down so it made a nice seal and then everything was cooked by steam. You turn the valve and give it 10 minutes then everything will be cooked. We’d make mash potato and fill metal bowls. Then the lads would come in with their plates and they’d get a big dollop of mash and cabbage. That was beautiful.

When everything was finished, say you were on cookhouse duties, the whole floor in the cookhouse had a very slight fall on it, so you’d start up at the top of the floor and then you would steam the tiles (they were tessellated tiles with a little knob sticking up, so you didn't slip). The steam would clean the tiles beautifully and because of the slight fall in it, all the water would go into a gully; give it 5 minutes and it all drained off.

“We’d make mash potato and fill metal bowls. Then the lads would come in with their plates and they’d get a big dollop of mash and cabbage. That was beautiful. ”

The RSM, Regimental Sergeant Major, he was in the centre of the square and he'd have you all round in one line, right round the edge of the square, and then he made you do arms drill.

It was all Lee Enfield rifles then and of course we had the bayonets on. The top of the bayonet come level with my jacket pocket and of course when I pulled it up to flick it up, the bayonet went through my pocket and there's me, 5 minutes later, trying to get the thing apart; I got three days jankers for that. Jankers was punishment where you would have a day’s work starting early in the morning, 6am, you had to get up and dressed, then you had to go down to the guard room, reporting for duty as your punishment, the guard commander would say: ‘right, get outside and wash this and the other out, dry it off’, make sure it's all done, now back up to the barrack room, would be about half an hour, because your mates were all going over to breakfast. So you had to scrabble round and clear your bed space up and go and get your breakfast and after you had your breakfast, you go back down the guard room and he'd give you some duties. The guard room in Germany, had cobbles in out in the front - we had to paint the joints in between the cobbles with black paint and then he’d find window cleaning, sweeping the roads up, all punishment because you got a bit bolshy one day.

A couple of my mates played up there. Once, when we were up in the Harz mountains, a mate got jankers and had to go on patrol, which was 10 miles out and 10 miles back, along the iron curtain, then when he came back, he had to get a blunt machete that was kept there and use it to cut through a big log. He wasn’t allowed to go to the evening meal until he cut through that. That was his punishment.

It worked as a punishment, you wouldn’t do anything again after that, you kept your nose clean as much as you possibly could.

“When he came back, he had to get a blunt machete and use it to cut through a big log. He wasn’t allowed to go to the evening meal until he cut through it - that was his punishment. ”

I’d done 100 miles in four days, with the whole battalion, up in the Harz mountains and we had hobnail boots on. I had a brand new pair because my others had split. That was murder marching 100 miles in four days with hobnail boots on. I had blisters all over the place and I didn't dare show them my blisters - you got charged for a blister because you had to be able to march. You each had a ‘housewife’, which is a repair kit that’s got darning wool in it, sewing kit and thimble etc. and I put some darning wool through one of the needles, and I pushed that darning needle through my blister - which was about an inch across and about half an inch high - I pushed it through until it came out of the other side. I pulled the wool through and then I cut the needle off and left a 2” bit either side of my blister and because that wool was inside my blister, the water inside it gradually came out, rather than you popping it and let it run out. You were still marching with blisters on your feet, but I had a tin of foot powder in each boot.

Being close to the Iron Curtain, we saw four men trying to climb the fence barrier from East Germany into West Germany.

The Russkies were in their century posts about every quarter mile - they saw and shot them and they were left there, hung onto the barbed wire.

I did 22 months over there, then the whole battalion came back and I was getting close to my demob when they decided that, because I had been in the building trade, I had to go up to Cumberland which is on the North Sea. I did 3 weeks up there learning all about civil defence.

The little town had been hit with an atomic bomb with walls blown out and floors hanging down. We had to pretend to be casualties and they dressed us up to look like our arms were hanging off and our legs was broken. The gang coming in had to learn how to treat us - put a splint on, like a figure 8 round your ankles to keep your legs straight as you were tied onto the stretcher. It was my blooming fate, I was at the top of the three-storey building which had all the floors but there was no stairs. I was tied onto the stretcher, and they made a jib out of some old timbers. They put that out with a pulley block on it and then they pulled on the rope and pulled me up in the stretcher. I was screaming because the rope was spinning. That was a good course and I learnt quite a lot of things. If war started, I'd have been in the Civil Defence Corps.

Cumberland was right on the Irish Sea and so cold. I got charged because I kept my pyjamas on underneath my denims. When you come to attention, there’s a gap on the side where your pocket is and that gap showed that I had pyjamas on. The Sergeant called me out and I had to jankers.

“The Russkies were in their century posts about every quarter mile - they saw and shot them and they were left there, hung onto the barbed wire.”

I got demobbed up there and I had to make my way back down, through London and got on the right train down to Semley at 3am. Of course, there were no mobile phones about in those days, and I couldn't find a phone box, so I had to walk four and a half miles up to Shaftesbury. I got up to Shaftesbury about 7am and banged on the door. Mother came downstairs in her nightie, opened the door, “yes?, ohh come on in quick, I’ll make you a cup of tea”, then she gave me an earful for banging on her door at 7am.

I enjoyed it though. Looking back, I wish I'd have signed on, stayed in the army but when I came home on leave, father had a building firm and wanted me to work with him. In those days you did what your parents told you. I built two schools, fire stations and a police station. I did 55 years in the building trade.

National Service made you look after yourself. They should have never stopped it, it made a man out of you and if you had a problem, you’d think about it and get on and do it.