It was a few days after my 18th birthday in September 1947.

A brown envelope dropped onto the doormat (inside was a four-shilling postal order, a rail warrant and instructions to report to Chichester barracks). I had been conscripted and given my first day’s pay. There followed an army number, a demob number and my AB64. When you are only just 18, two years is a long way off. I wasn’t thrilled about going but it was just something that we all had to do.

On arrival, there was a trip to the Quartermaster’s stores for kit issue, trip to the Doctor for a limb count and TAB, aptitude tests and an introduction to the wooden hut that was to be our home for the next six weeks. A large barrack room with about thirty beds. Sergeant’s bunk at one end and a fuel-less Glow-worm stove in the middle. I sat on my biscuits (hard mattress) to study what the Quartermaster had given me. It was a long list and included a battledress, ancient and ill-fitting denim overalls, boots, lots of webbing, two shirts and underclothes, 4 pairs of socks and a greatcoat. Nearly forgot the Hussif – needle and thread, darning wool and some spare buttons.

“When you are only just 18, two years is a long way off. I wasn’t thrilled about going but it was just something that we all had to do.”

Time was no longer my own. We had to get our kit blancoed and spit and polished. Everything marked with my “last four” and packed into the large pack. The Sergeant showed us how to march about and what to do on parade. In short, everything a budding soldier should know. The first thing to do with a new pair of boots was to destroy them. This was accomplished with lots of boot polish, spit, a toothbrush handle, plenty of time and a hot iron. After a bit we were issued with rifles. More to learn and something else to polish.

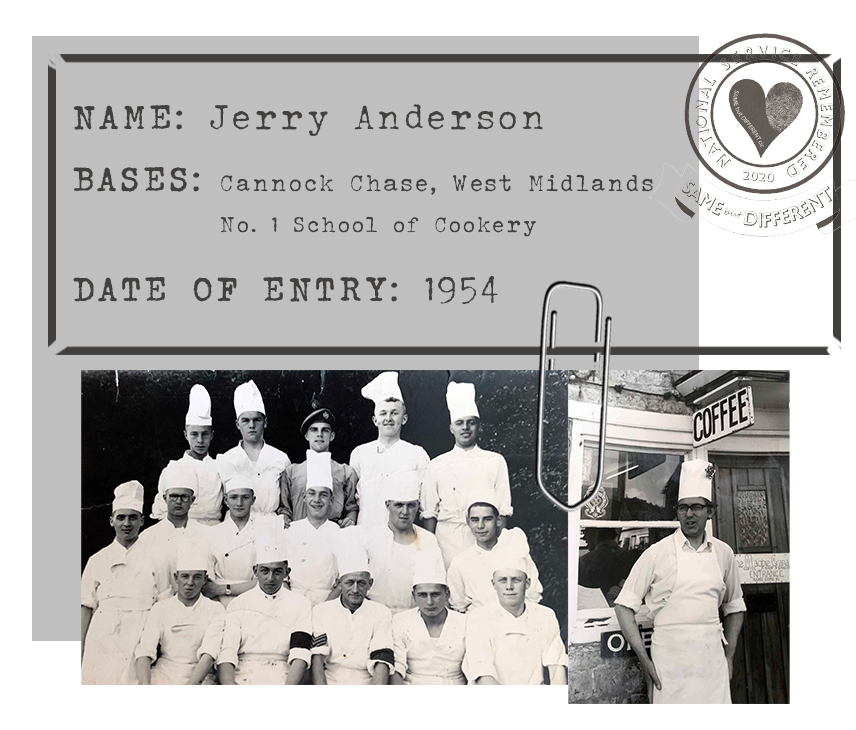

Wastewater from the cookhouse was sent through a series of baffles which allowed the fat and grease to float to the top where it could be scooped up and sent to the Brylcreme factory.

Friday was pay day - 28 shillings.

We had to buy our own blanco, Duraglit and boot polish. Not a lot left for tea and Eccles cake at break times or a couple of Woodbines. Nearly everyone smoked. Food was plentiful and very basic. Doled out into one mess tin and tea into the other. If you managed to be towards the front of the queue, you could be early at the washing up bucket.

We were asked into which arm of the Army we would like to go. The choice was infantry, tanks or signals. The latter seemed to give a better chance of an interesting and quiet life. So I was packed off to Signals School at Catterick. I was to be an OKL – Operator Keyboard and Line. In effect, a typist on a teleprinter. Freezing classroom, typewriters with the keys blanked out typing groups of five random letters, as used in ciphers, to music from a dilapidated gramophone. We learnt to type with all ten fingers. If, and when, deemed proficient, we graduated to teleprinters.

“Food was plentiful and very basic. Doled out into one mess tin and tea into the other. If you managed to be towards the front of the queue, you could be early at the washing up bucket.”

I was sent to a WOSB – War Office Selection Board – which took place at Hazelmere in Sussex.

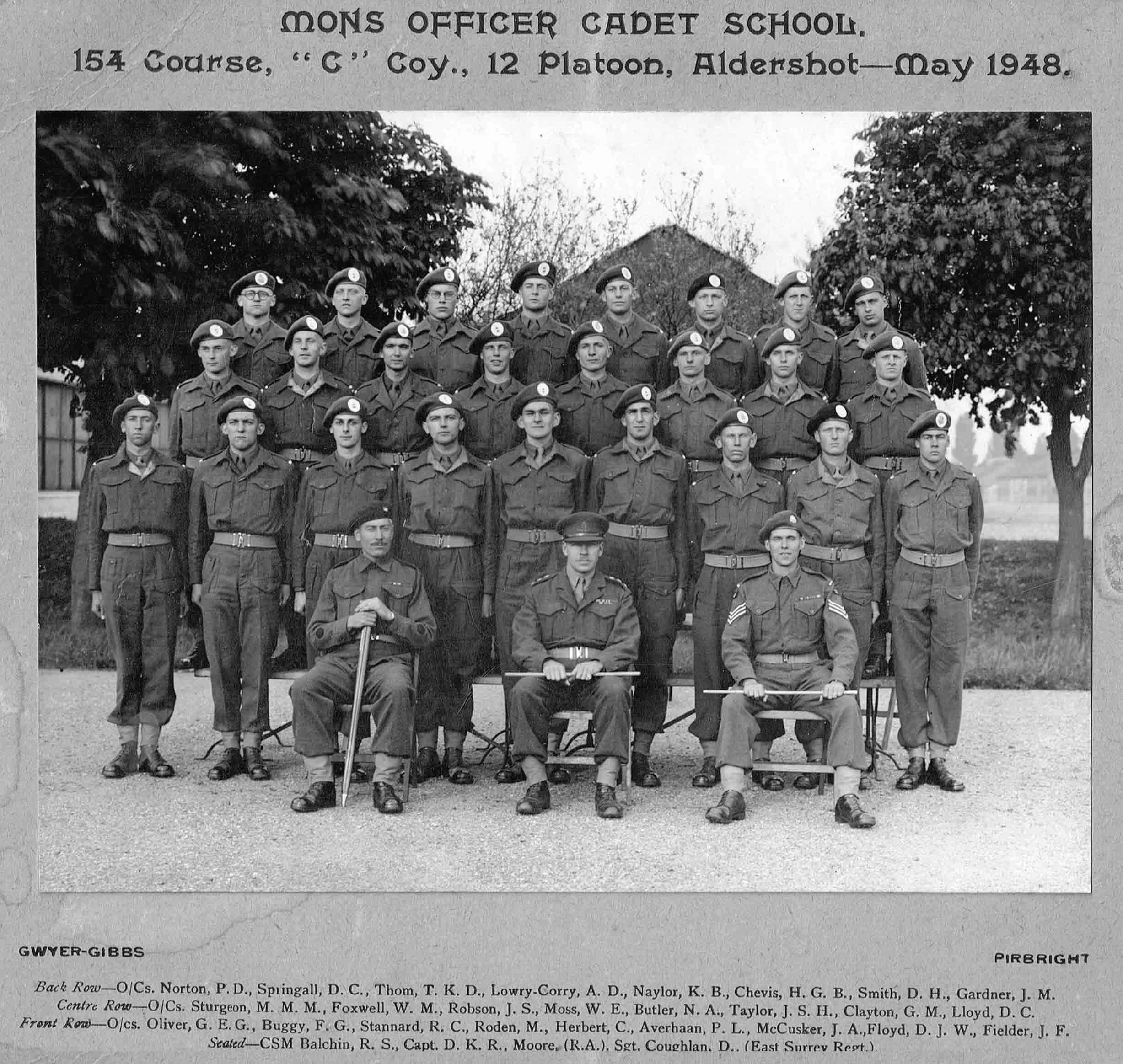

A few days of interviews, intelligence, initiative and leadership tests. A pleasant change from the mindlessness of Catterick. I passed and was deemed suitable for promotion to a second lieutenant. But first, six weeks at Mons Barracks in Aldershot with RSM Brittain and then twelve more weeks at Signals School in Catterick. Halfway through the Catterick bit I was given my pip. Goodbye to prickly shirts, hello to 13 shillings a day, sheets on my bed and Prince Charles. The 13/- was not much of an increase as we had to buy our own uniform and pay mess bills. I learnt a lot about how wireless, teleprinters and telephones worked and I got quite good at Morse code. As for TEWTS (Tactical Exercises Without Troops), they gave me a driving license after a week on the aerodrome with a 15cwt truck. I still have it. The mountaineering club was a good wheeze. It involved climbing into a three-ton truck on Friday evening; destination a barn in Langdale where enthusiasts could risk their lives on the crags and the sensible ones relax below. One evening we were troubled by a car flashing its lights and driving far too close. We gave as good as we got with gestures and shouts while clinging on to the dangling rope at the back. Managed to shake him off. The driver turned out to be the General in charge of the North and so ended the Mountaineering Club.

“Halfway through the Catterick bit I was given my pip. Goodbye to prickly shirts, hello to 13 shillings a day, sheets on my bed and Prince Charles. The 13 shillings was not much of an increase as we had to buy our own uniform and pay mess bills.”

We were asked where we would like to be posted to.

I suggested Washington or Tokyo where there were R Sigs outposts. They sent me to Lisbon which sounded great until they gave me a travel warrant to Lisburn in Northern Ireland. I sewed my bird’s nest badge to my battle dress and settled down in “D” mess where junior officers were billeted. Our NID (Northern Ireland District) badges were mocked as cuckoos in the nest so had to be replaced with harps. “D” mess was much more comfortable than any barrack room. I had a small room to myself with a tiny electric fire. There was a primitive bar and a snooker table. A batman who saw to blanco and boots. I soon acquired a bicycle which enabled me to go exploring. I had no idea what my military function was. I belonged to a fairly large Signals establishment at NID HQ. There was a colonel in charge whom I never saw, a major who appeared to do everything, a captain who acted as adjutant and me. I discovered that I was also MT officer in charge of unit transport. Everything was ticking over nicely under the Lance Corporal. Quartermaster too which involved a daily trip to the stores to sign requisition documents under the watchful eye of the Sergeant in charge, Sports officer was really a sinecure as there was an enthusiastic lance corporal. Education officer was a puzzle – who and what and how? My ambition was to study medicine but I had fluffed my higher certificate in Biology. All was not lost. As Education Officer I was able to organise a course at Queen’s University and as MT officer I could arrange transport. I was able to retake biology and ease my way along the medical pathway.

“I suggested Washington or Tokyo where there were R Sigs outposts. They sent me to Lisbon which sounded great until they gave me a travel warrant to Lisburn in Northern Ireland. ”

The invisible Colonel had his funny ways. Once he ordered six Command vehicles which he parked in the open outside the RASC transport sheds under the charge of the MT officer. Six months later he decided to send them back only for the MT officer to discover that the RASC had used them as a source of spares. I had visions of paying off the deficit from my 13/- a day for the rest of my life. Don’t worry said my Lance Corporal, I’ll fix it. And he did. What he couldn’t steal back he made. Screwdrivers, spades and tarpaulins were his speciality.

My demob number was 120 and gradually the day was approaching.

Our Colonel had been instructed to send an officer on a cypher course in Catterick. On arriving at the School of Signals, I was invited to sign the Official Secrets Act. I explained that I was leaving the army next week and didn’t wish to be encumbered by any of its secrets. Before I could say Jack Robinson, I was sharing a Pullman compartment on the way home with some kindly professors returning from a British Association meeting in Edinburgh. Must admit to some schadenfreude as I imagined the explaining the Colonel would have to do.

I was lucky in a way as I had experience of living away from home and had been a cadet. Even more lucky in that I was not involved in any fighting – be it Malaya, Borneo, Palestine, Kenya, Suez. I left the army with some knowledge of wireless, telephony and teleprinters; ability with touch typing and Morse code; a profound respect for Lance Corporals; an aversion to institutional life; and a demob suit.

A couple of anecdotes? The time I was given a loaded gun and sent to collect the imprest money from the bank. A teenager with a loaded gun and a bag of money for the British Army in Northern Ireland – could have started WW3.

A teenager strolling down Whitehall in the middle of the night with my lonely pip. A clanking of armour, a stamping of horse and waving of sword as the Household Cavalry saluted me.

Did it do me any good? Did I do the country any good? Did I do the Army any good? Who am I to tell? We ex National Service boys were more mature when we entered University. We had had a two-year gap year without any hedonism. Having left the service, I continued on my medical journey and enjoyed a career in General Practice.