I left school at 14 and went on the farm to work because everybody worked on the farms round here.

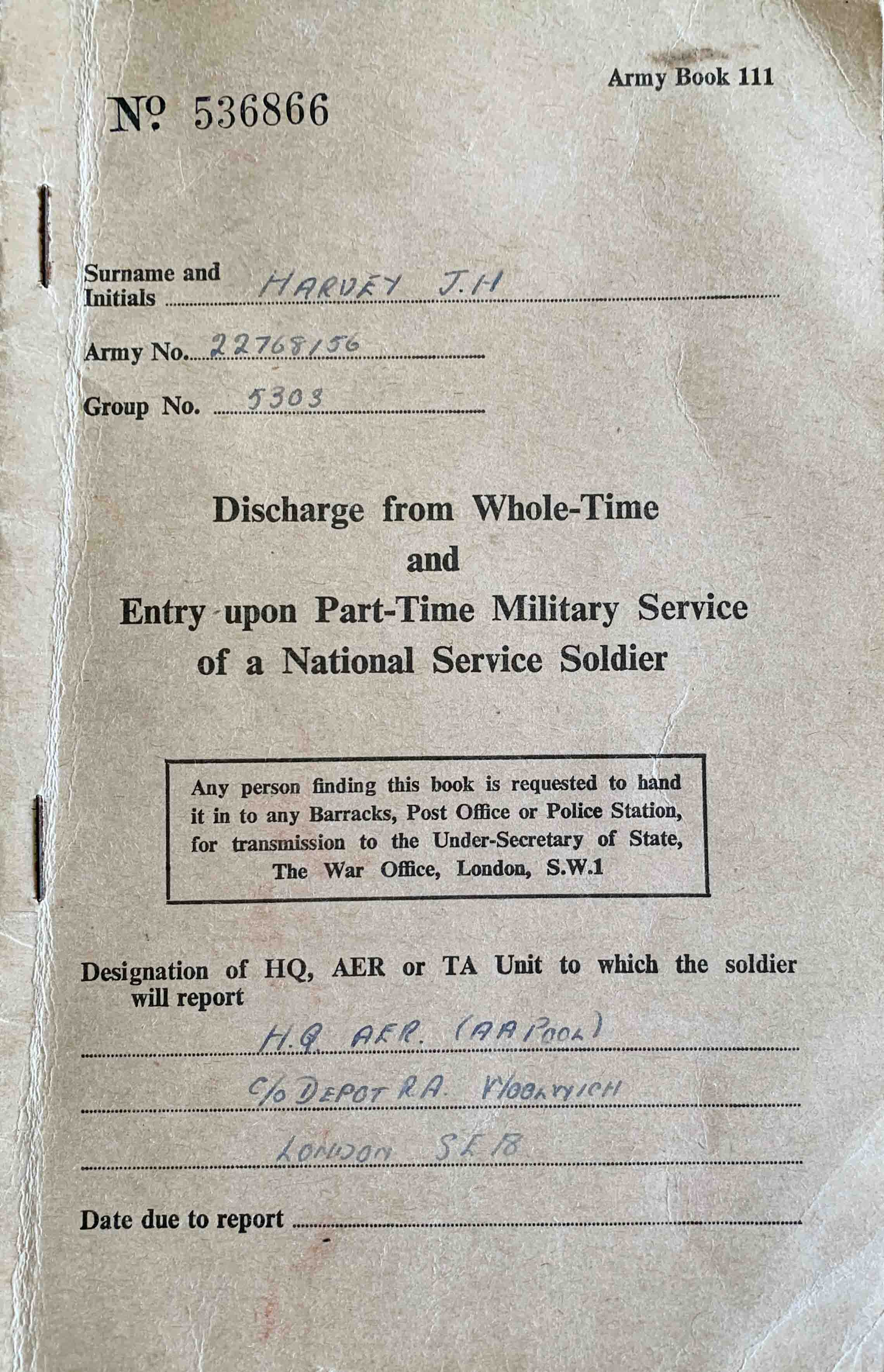

Initially, we had to go and register. I hated the thought of it, nobody wanted to go in the army. We all had to take our clothes off, everyone walking around in this hall with nothing on, getting measured and everybody's looking at you. When we left, they said, “well, that's it you'll be hearing from us”, which we did.

Before I went to register, I left the farm. The farmer said to me “you can stay on the farm and I'll keep you out of the army” but I said “no, I hate going but nobody's going to call me a coward for not putting on a Queens uniform or helping their country if they need it, I'm man enough for that and I want to learn something”. So, I went and worked in a garage for about month. Then one morning, my father was the school master and the school bus went there, picked up all the kids and when it came back, the bloke who was driving the bus worked for the garage where I was and he said “here, the Queen wants you”. He gave me an envelope from my father that had my call up papers in it, so that was that and I thought ‘oh dear, oh dear’.

We had to go up to Gobowen and then get on a train. Didn’t have a clue where we were going. Luckily, there was another lad, two villages away, who was going the same time, so we went up together.

I’d never been anywhere away from home and I was one of those blokes, even when I was a kid, I would never go home if nobody was there. I’d sit in the rain or snow, never indoors - mother was a bit worried about it. We got off the train and all I could see was buses and lorries. I was used to the quiet of the country.

“The bloke who was driving the bus worked for the garage where I was and he said: “here, the Queen wants you”. ”

We pulled up and this man came up to me, with a stick under his arm, asked if I was for Parkhill camp and told me to get on the bus. They took us in, gave us a cup of tea and a fancy cake and I thought ‘This aint bad going’. It was getting dark then, it was February when I went in, and it was cold up there in Shropshire. We had our food and had a walk around; we’d been travelling all day and it was getting dark. We were then taken into a big shed, with blokes sat behind desks. One asked me what size my head was, I had no idea. He gave me what looked like a dustbin lid and said “put that on, that’s your hat”. Another had the boots and another had the trousers and jumpers. You had your case in one hand and they laid them all over your arms. It was gone midnight when we got back to our billet, which wasn’t very warm. On the bed, there was a piece of paper. Then the old Sergeant came in and said “take off all of your civilian clothes and send them home to mummy because you won’t be going home to see her two years”. I heard men crying, wanting to go home. Anyway, I had been in the Army cadets and I was always a shooting man, I knew all about guns and everything, they couldn't tell me nothing about that.

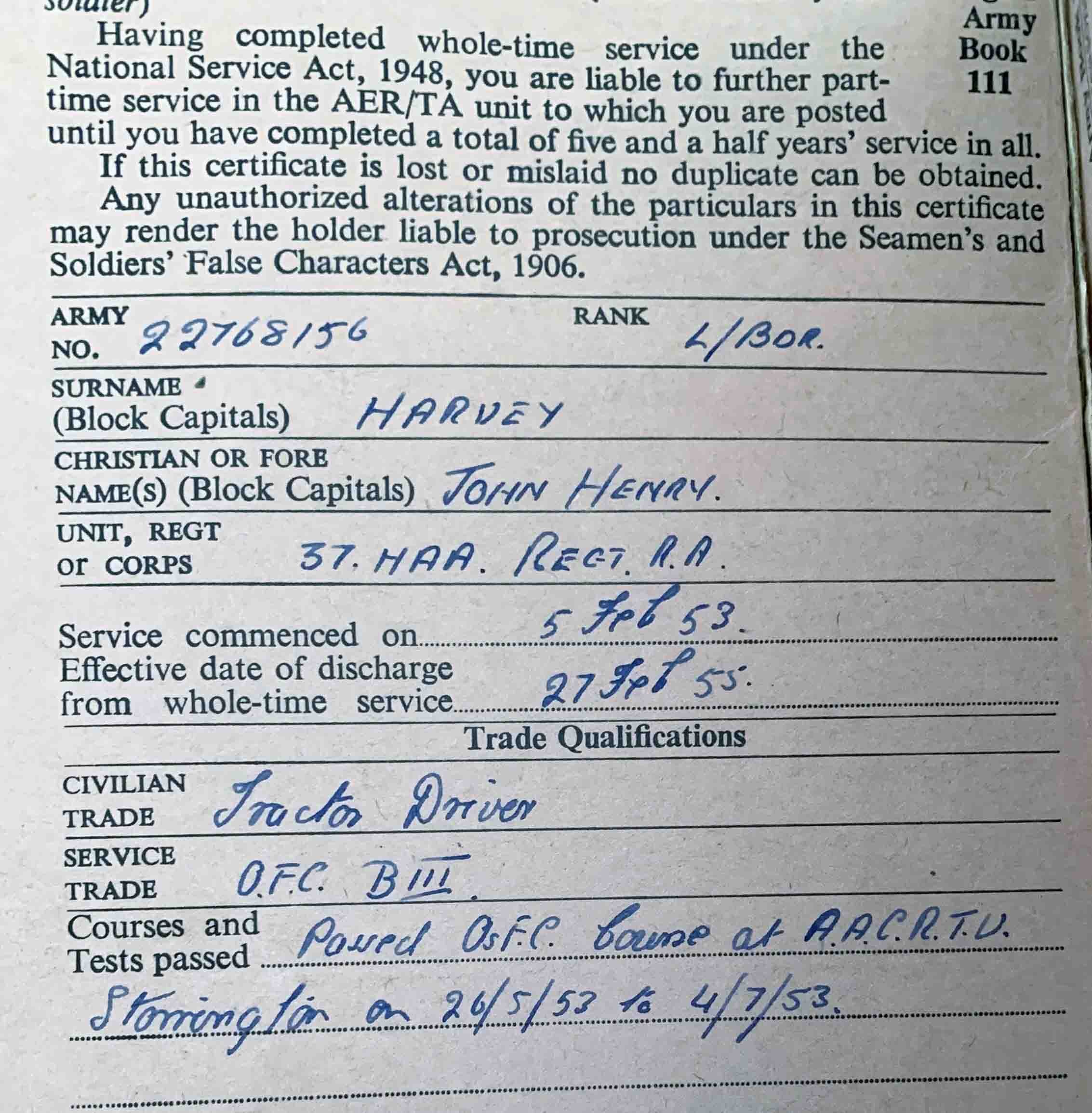

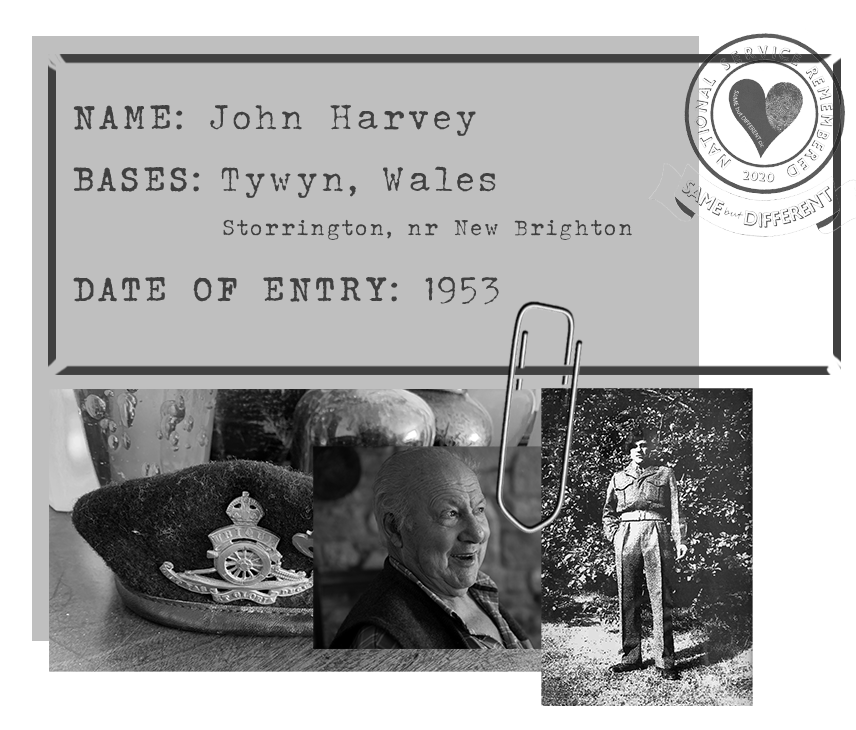

We then got transferred up to Tywyn, Wales.

Dear oh dear, we were firing out there 37s and 45s. Big guns. We had to take a test to see what we were going to do. I wasn’t very brainy, I'll tell you, but he came out and said, “you’ve passed, you’re going to be a radar operator”. I’d been working on a farm, I had no idea what radar was! So, we did 15 weeks basic training up there in North Wales and thought we’d get to go home on leave, but they said, “no, you’ve got to go and do your radar course now down at Storrington near New Brighton”. It was not too far from home really and a couple of mates came up on their motorbikes to see me. We went out on the Saturday night and got drunk. Then it was back to camp until my course was over.

I met a bloke in the army who was a real hard man, he was always fighting. He came from Exeter and went into the PTI.

Anyway, I was bringing him home on leave with me because he was a good chap. He looked after me. But then he went and got married. I was going to be best man at his wedding down in Wales somewhere, but the night before, he come back to the camp and he pinched my money. I didn't know it was him. I went off down to the wedding down in Wales then came over on 2-3 days leave. The last night I was at home, I went out and when I came back, I sat down on the settee in mum’s room - I didn't know but he was behind the settee. He’d broken in there and took some stuff. I didn't know until some bloke in the village told us. I’d brought him home and he’d got to know one or two people so they knew it was him.

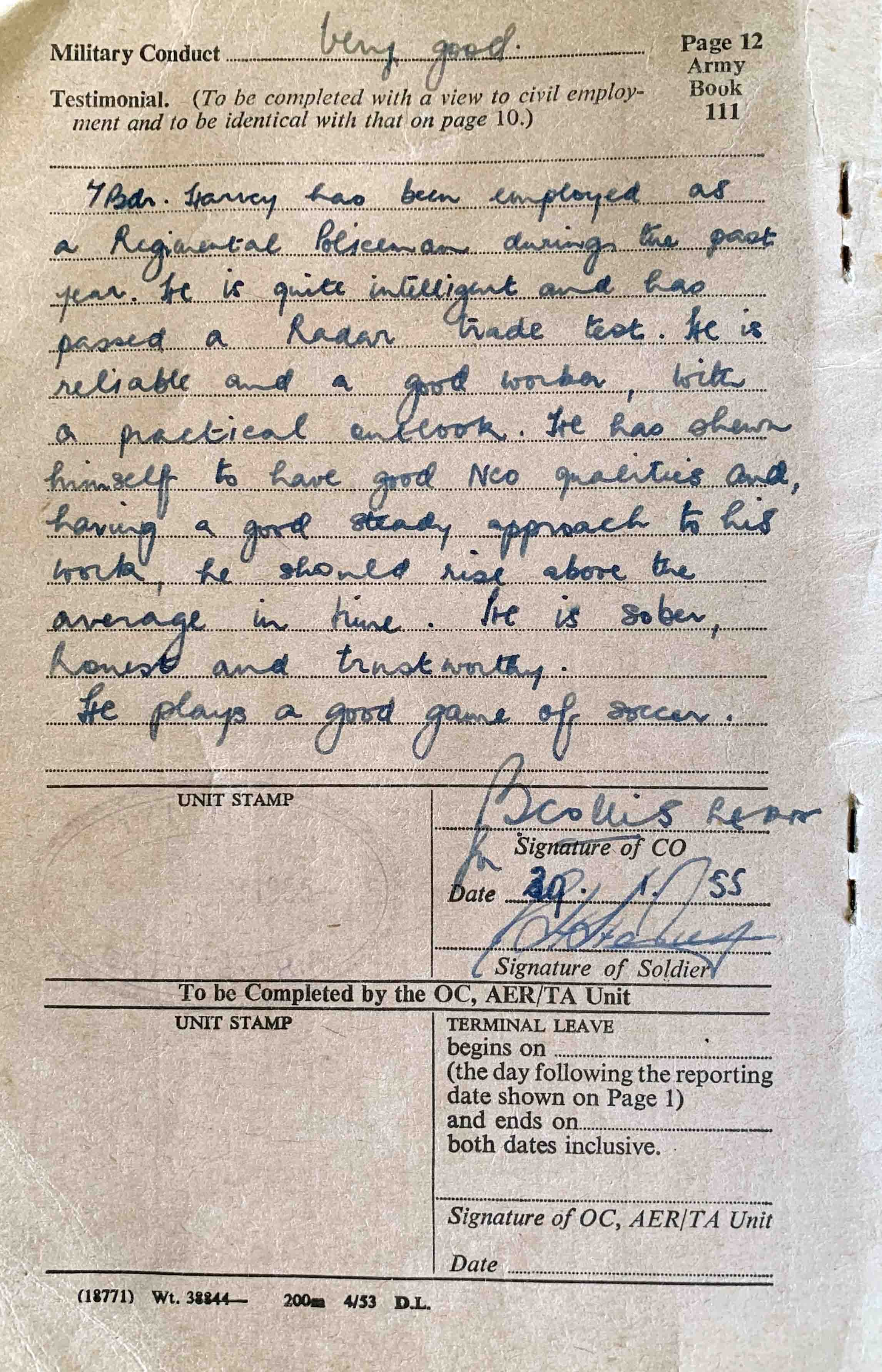

So then I was back in the army and I’d been put in the police department – after a while they don’t ask you, they tell you what you’re going to be. Of course, when this bloke came back off leave, I had to take his pass and the civilian police came up there. The RSM had called me, and he said, “don’t worry about anybody else, you do what you’ve got to do”. He said “tonight, when he goes back home, you’re to go back on the train to town. I want you to get on the train because he will be arrested by then, and you will go down to pick his wife up and take her in to the police station”. I’d been best man at his wedding about a fortnight before. So anyway, I did that and he got three years inside for it. It was hard for me, he was a good mate of mine.

“I wasn’t very brainy, I’ll tell you, but he came out and said, “you’ve passed, you’re going to be a radar operator”. I’d been working on a farm, I had no idea what radar was!”

It was a Garrison military police.

There was two regiments in the camp but it was pretty quiet. The only thing we had to deal with sometimes was trouble with the IRA. They used to come over and everything had to be locked up so everyone was on tenterhooks.

I finished at my time in the police, under the RSM. There was nobody else in charge of it. I did my two years. I did try to go in the Navy, I tried to go into any route to get out of England but ended up in Wales! I was a good footballer and played for the regiment and I could shoot anything. They also had me throwing the hammer and discus. They then tried to teach me the pole vault. I started running and stuck the pole in the hole. I was going up and up and up so I let go of the pole and broke it all to pieces. It didn’t go too well so I got out of that.

I knew the Lieutenant in charge of our battalion. He was really good and I’d go and see him every 6 weeks. He’d say “Harvey, you’ve come for a pass haven’t you”. I said “yes, I want to go home for a fortnight”. He’d say “you can't do that, you can go home for a weekend”. So I’d come home from Wales on a Friday night, back to Bournemouth. Travel all night and get home on Saturday morning. Go out Saturday night and then maybe if I had 48 hours or 72 hours, whichever one, but then I had to go back on Sunday or Monday night. Travel all the way back up there again but I didn’t care, I could stand it, so I did it.

“I did my two years. I did try to go in the Navy, I tried to go into any route to get out of England but ended up in Wales! ”

I learnt all I could in the army.

You know what you’ve got to do and why you’re there, you’re not there for games. You are there for something which is deadly. You learn to fight and protect, and protecting people means kill or be killed in some cases. We never got to that state where I had to go to war but we had all the training, fighting with a bayonet and shooting. The closest I came to fighting was a bloke had a go at me and he had a big bayonet. He hit me with the rifle and knocked me on the floor. It was a wooden floor and he poke me in the back and he stabbed me but I moved my leg a bit and he stabbed me to the floor. So I got up off that, and I nearly broke his back. I thought you won’t ever do that again to me. Other than that, nothing happened, so I did my time but I must admit I wouldn't have missed it for anything.

I really enjoyed it. You could go in there and be an idiot, not doing anything but it was a chance to learn a lot of things that I could never learn round here on the farm. A lot of the things they taught you was cleanliness. A lot of blokes went in there and they'd never worry, their clothes were all flung over the floor and everything. They were dirty themselves. I wasn’t terribly untidy but it taught me to always be clean and tidy.

“You know what you’ve got to do and why you’re there, you’re not there for games. You are there for something which is deadly.”

I've run all over the Brecon Beacons, where the SAS go. Did training down there and up on Snowdonia. I remember going out for a run in the marshes, out on a march, and we stopped at a little farm, sat out and had a nice chat on a milk stand. I wrote my name on the wood at the back of the milk stand and the girl there wrote me a letter. I didn't reply back because I wasn’t going to stay around out there, you know, and I didn't know how to find her anyway.

They used to take us out with a compass. I never knew what to do with a compass, so they took us out all out up Snowdonia. They dropped you off two at a time from a lorry and it would go further. “Sit down” I said, “there will be a bus along in a minute”, so we caught the bus to the railway station. Got on the train and went back to camp and that was that.

If you make a friend in the army, that friend is a friend for life because you rely on him and he relies on you. If you’re in trouble, doesn’t matter if you’re right or wrong, he’ll stand by your side. Simple as that. And you need that, because if he doesn’t, your dead.

But I enjoyed it, I did enjoy it.

When I came out, I had to earn some money because I'd had two years of having nothing. I went to work in a Brickyard, which was hard work, but I was as fit as anything. I worked out there, digging clay all the winter then made the bricks in the summer. Then I got a job on the Southern Electricity board and spent 12 years with them, making my way up to second in charge. When I left that, I started up a business on my own, contract fencing.