What matters most?

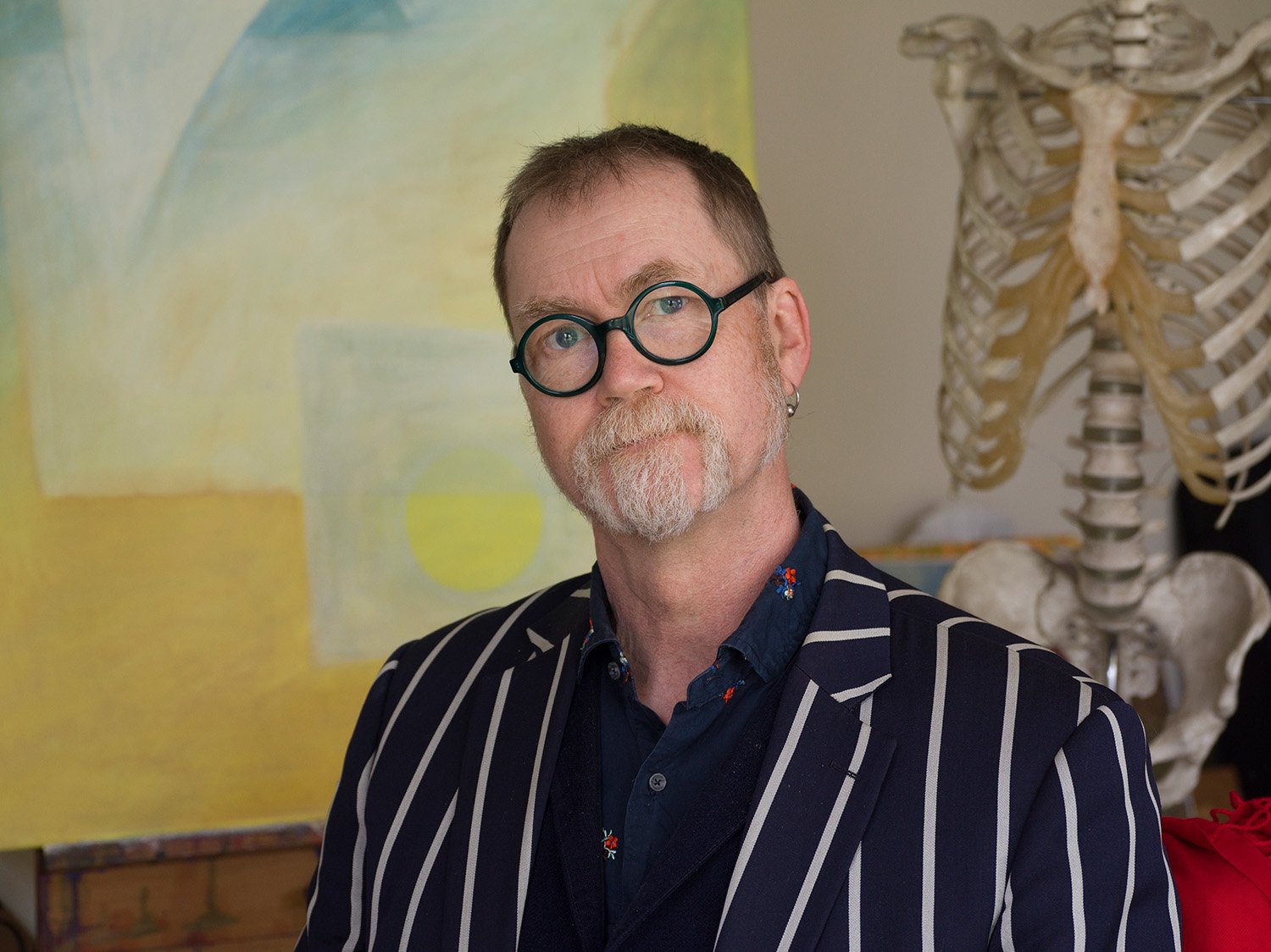

Dan

Dr Dan Muckle-Jones has worked as a general practitioner in Mold for nearly 30 years. Through his time as a GP, he was at the centre of the local community and saw various generations of families come through his care.

He decided to retire nearly 10 years ago, and although he felt it difficult to leave his patients behind, he felt it was the right time for him to move on.

“The truth is, I miss it. I don't miss all the pressure, but I really miss the people. I do often have feelings of guilt about leaving the profession because I sometimes think that I have more to give. Interestingly, I think I still have that caring need in me and I'm glad I retired because that caring role has been fulfilled to a large degree by my family. My mother-in-law has Alzheimer's, and we've been supporting my brother who has mental health issues; plus now, we have a seven-month-old little rescue dog, who takes up a lot of my energy at times.”

Dan’s mother was a nurse and his father was a doctor, so the family had an ethos of caring for others. His ‘Nain’ (grandmother) was a district midwife who covered much of Caernarfonshire, cycling around on a bike. With the medical profession being a big part of his life from a young age, Dan went into medicine at Cambridge and then St. Thomas's in London. He particularly enjoyed his clinical training.

“As a child growing up with my father as a GP in Harrogate, in the 1960s, we would have people knocking on the back door with nails stuck in their fingers and all sorts of minor injuries and traumas. My father would be getting up in the middle of the night to drive off to Pateley Bridge to see patients. I think if my father had a fault, it was caring too much. As my medical career progressed, I became far more interested in people rather than diseases. I became interested in the whole holistic sense of caring which led me to be drawn to training in general practice.”